WASHINGTON – JULY 27: President Ronald Reagan addresses the nation on Tax Reduction Legislation … More

Getty ImagesIn the final big 2025 budget bill, Senate Republicans worked hard to make permanent several expiring corporate tax provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) .

They succeeded by adding deeply controversial cuts in Medicaid to help fund the tax cuts and by changing the way Congress scores revenue measures to make their bill appear relatively costless even though it would reduce federal revenues by nearly $4.5 trillion over the next decade.

But all that effort may all be for naught. Historically, controversial tax changes rarely are permanent. And that may be especially true for the Senate’s efforts.

Not What You Think

On paper, the argument for permanent investment incentives is sound, especially if the goal is to boost long-term investment. Businesses can’t project the true return on their investments without knowing how they’d be taxed in the future. Absent such tax stability, they are reluctant to make these purchases, weakening the economic benefit of the tax breaks.

But in Congress, the declared lifespan of tax changes may not mean what you think. Lawmakers have a long history of repeatedly extending temporary tax breaks. And they rewrite what start out as permanent tax provisions almost as often.

Limited Shelf Life

Among the reasons: Tax changes enacted on a strictly partisan basis, such as the current budget bill, have a limited shelf life. Should Democrats take control of Washington, many of these business tax breaks would be in jeopardy.

Lawmakers may be under added pressure because this massive budget bill is expected to add more than $4 trillion to the federal debt that already was expected to top $52 trillion in a decade. In that environment, it is a good bet that taxes will have to be increased, just as spending must be cut.

As a result of GOP budget cuts and Trump Administration staff reductions, the IRS has limited capacity to write regulations or enforce the laws. This may amplify the public perception (and perhaps the reality) that corporations are gaming the tax system, giving Democrats leverage to repeal, or at least scale back, some corporate tax breaks.

But the main reason the budget bill’s tax provisions likely will not be permanent is that the tax law is evanescent. But the political system creates incentives for lobbyists and lawmakers alike to change tax laws. Just as stock traders need volatility to thrive, so does the political system.

A History of Change

Just think about the history of major tax bills.

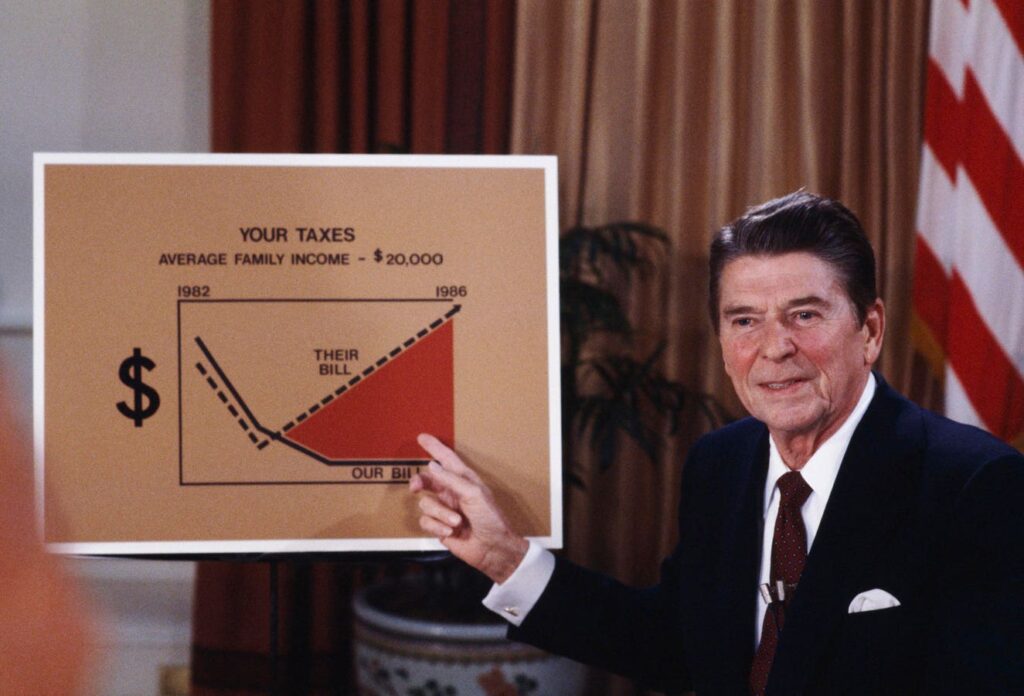

Congress substantially rewrote the federal income tax code in 1954 and 1969. Then President Reagan drove Congress to adopt his historic 1981 tax cuts.

But, with even the White House worried about deficits, Congress largely undid them with tax increases in 1982, 1983, 1984, and 1987. Some provisions of the largely partisan ’81 bill were repealed before they even took effect, and the 1982 rewrite was among the largest tax increases in modern US history.

In 1986, Reagan engineered a widely praised fundamental rewrite of the federal tax code that passed with broad bipartisan support. But it didn’t take long for Congress to rewrite even some of its most important elements.

For example, the ’86 Act cut the top individual income tax rate to 28 percent. It lasted less than five years. In 1991, Congress raised the top rate to 31 percent. By 1993, it was 39.6 percent.

That top rate survived nine years, a lifetime in tax policy. But in 2001, at the urging of President Bush, Congress lowered the rate to 35 percent. By 2012, it was back to 39.6 percent. Five years later, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act trimmed it to 37 percent.

The On-Again, Off-Again Investment Credit

Corporate taxes are not immune. Take, for example, the investment tax credit (ITC) that allows firms to immediately write off a share of their capital costs. In 1962, Congress enacted what it called a permanent 7 percent credit. In 1964, Congress kept the rate but liberalized the rules. In 1966, it temporarily suspended the credit, before restoring it in 1967, and repealing it in 1969. In 1971, President Nixon, who had called for repeal two years earlier, convinced Congress to bring the credit back on a temporary basis, but at a 10 percent rate.

The ’81 law created a new way for businesses to depreciate the cost of their plant and equipment. That system lasted for five years, before the ’86 Act created yet another depreciation plan.

Today, most remaining investment credits are limited to green energy equipment. And the budget bill would repeal them. Yet, the broader, permanent expensing provisions in the new Senate bill are, in a sense, step-grandchildren of the old ITC.

The congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimates the permanent business provisions of the bill would increase the deficit about $700 billion over 10 years

Acknowledging the true 10-year cost of these tax benefits is a sound fiscal decision. But businesses would take the bill’s promise of perpetual tax treatment at their own peril. In the words of Willie Nelson, “Nothing lasts forever but old Fords and a natural stone.”

Read the full article here