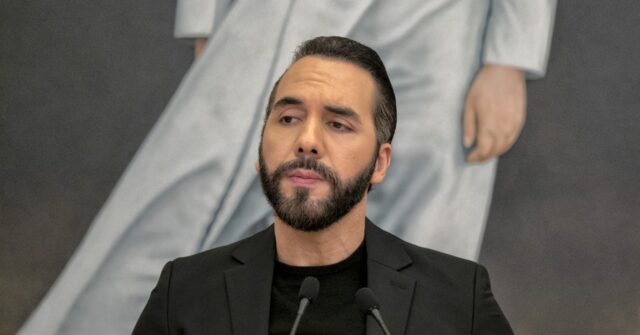

Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele condemned critics of his political party’s decision to end presidential term limits in the country, noting in a message on Sunday that the vast majority of “developed” countries allow the indefinite reelection of prime ministers and claiming any concern is in bad faith.

“90% of developed countries allow the indefinite reelection of their head of government, and no one bats an eye,” claimed in a message published on the social media site Twitter. “But when a small, poor country like El Salvador tries to do the same, suddenly it’s the end of democracy.”

El Salvador’s Legislative Assembly voted to amend the nation’s constitution on Thursday to end all presidential term limits, ending a precedent set in 1841. In addition to allowing the public to vote for the same president in perpetuity, the reforms ended the runoff election system, in which a candidate must obtain over 50 percent of the vote to win the election or else face his closest rival in a second election featuring only the top vote-getters in the first round.

Bukele already flaunted the presidential term limits in 2024, winning reelection by using a loophole in which he resigned from the presidency six months before the election to legally appear on the ballot. The president was first elected in 2019 and enacted sweeping national security reforms to eliminate the influence of criminal gangs on the country. The reforms have proven to be tremendously popular and Bukele won reelection with 85 percent of the vote in 2024, in an election the Organization of American States (OAS) certified as legitimate.

In his message on Sunday, Bukele referred to the indefinite reelection of prime ministers in most developed countries. He addressed the fact that parliamentary and presidential systems are different by describing any appeal to that fact as an attempt to obscure a “double standard” against small countries such as El Salvador.

“That’s just a pretext … Because if El Salvador declared itself a parliamentary monarchy with the exact same rules as the UK, Spain, or Denmark, they still wouldn’t support it,” he argued. “In fact, they would go ballistic if that happened.”

“Why? Because the problem isn’t the system, it’s the fact that a poor country dares to act like a sovereign one,” he concluded. “You’re not supposed to do what they do. You’re supposed to do what you’re told. And you’re expected to stay in your lane.”

The term “developed” country does not have any formal recognized definition in international law. The United Nations identifies the world’s “major developed countries” as the members of the G7: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Only one of these countries, America, has term limits, which would put the rate at 86 percent.

Most countries widely accepted as developed are in Europe, where parliamentary systems with no term limits on the prime minister are most common. The World Trade Organization (WTO) allows countries to choose how they identify, however, which distorts the generally accepted list of developed countries. China, for example – the world’s second-largest economy and largest manufacturer – identifies as “developing” and benefits from programs intended to help “developing” or poor countries despite its status as an economic powerhouse. China, a communist dictatorship friendly to the Bukele government, does not impose term limits on the chairman of the Communist Party, the head of government.

The rapid advance of constitutional changes in El Salvador were made possible not just by Bukele’s personal popularity, but by the tremendous success of his New Ideas party in the legislature. The federal lawmaking body only contains six politicians not officially in Bukele’s party at press time; three voted against constitutional changes last week. Prior to Bukele, El Salvador was typically governed by one of two major parties: the center-right Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) and the leftist Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). Bukele began his political career as a member of the FMLN but was expelled from the party in 2017, two years before winning the presidency, for allegedly being too disrespectful to fellow party members.

Bukele himself, independent of his party, remains extremely popular due to his anti-gang policies. For years, the president has maintained a “state of exception” in the country that dramatically increases the power of law enforcement to detain individuals considered a security threat, allowed Bukele to build a massive prison complex for gang members, and technically limited some civil rights, such as freedom of assembly. The complete domination the gangs enjoyed over the daily life of Salvadorans prior to the state of exception, however, imposed a far greater limit on the individual freedoms of citizens, according to reports published even in opposition media outlets. El Faro, one of El Salvador’s largest newspapers and a consistent opposition voice against Bukele, reported in 2023 that, thanks to Bukele’s policies, the gangs “do not exist” anymore as they once did, allowing citizens to enjoy public spaces such as parks and beaches.

With the gang problem increasingly close to a complete resolution, Bukele has focused in the past year on consolidating power, alarming some international observers – as he conceded on Sunday. The president has yet to use that power, however, to silence dissent, defeating opposition leaders in the ballot box instead. El Faro has continued to operate freely despite its open hostility to Bukele, for example; its pages on Monday featured an exasperated article calling for the international community to move faster in condemning Bukele as a dictator.

The OAS verified Bukele’s victory in February 2024, acknowledging that the situation surrounding the election was “unprecedented” but that it had “no doubts” that Bukele won the election legitimately. OAS observers urged Bukele to undertake “a responsible and deeply democratic exercise” in the face of the unprecedented power the people had given him.

“This will be decisive to guarantee the future of democracy in El Salvador,” the regional body noted.

Follow Frances Martel on Facebook and Twitter.

Read the full article here