This article was produced by National Geographic Traveller (UK).

I didn’t anticipate starting the day by accidentally slapping a jellyfish. Yet it’s hard to maintain a personal sense of space underwater when surrounded by dozens of these pastel-pink, deceptively ethereal creatures. As they pulse and undulate around me in the serene waters of the Andaman Sea, my unintended victim floats away, seemingly unfazed — but that brush sends my limbs into uncontrollable panic, like branches buffeted by a hurricane.

Head above water, however, everything is a lot more sedate. I’m surrounded by gargantuan, tree-clothed karst towers — limestone rock formations that characterise this western coastline of southern Thailand. The cliff rearing immediately to my right looks particularly magical, almost superimposed. It juts out into the cerulean blue sky — which is softened by specks of pink and purple clouds — and stands tall like a phantasmagoric giant watching over as I attempt to navigate the waters at its feet. The only sounds are the cricket-like trills of birds taking their morning flight, and the gentle splashes of water hitting the side of our boat.

The famous Maya Bay was closed between 2018 and 2022 to combat catastrophic damage to the fragile sea floor caused by repeated dropping of anchors. Photograph by DanitaDelimont, AWL Images

It’s currently a little before six in the morning and we’re docked in the northern part of Maya Bay, a protected area belonging to the small, uninhabited island of Phi Phi Leh. Along with just 10 other guests, I’m on a seven-day sailing trip with Intrepid Travel, aboard the twin-hulled catamaran, Cataleya. It’s only the fourth day of the trip, but I’ve already admired the stalactites of Ko Phanak Island’s Ice Cream Cave (so called because of their ‘melting’ appearance), kayaked through pristine waters of the Hong Islands and witnessed an impossibly photogenic sunset on Railay Beach while a colony of fruit bats darted around above my head.

Maya Bay is arguably one of the most famous stops on our journey, surrounded as it is by dramatic cliffs and a picture-perfect white, sandy beach. Our captain Rob Williams has us snorkelling here at the crack of dawn to beat the cacophony of longtails and speedboats that will arrive in an hour or two. Everything changed in this area back in 2000, when Danny Boyle’s blockbuster film adaptation of Alex Garland’s cult-classic novel The Beach, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, included key scenes at Maya Bay. The film’s success spurred a period of crippling overtourism. Some days, as many as 4,000 tourists would arrive at Maya Bay by boat and the repeated dropping of anchors caused catastrophic damage to the fragile sea floor. The Thai government finally took action in 2018, closing the bay until 2022 to help facilitate marine regeneration.

“This is the quietest I’ve ever seen Maya Bay in my entire life,” Rob says in a thick South African accent, as he bobs up and down in the water. One of the many perks of having our own boat is that it allows us to sail to the rhythm of our own timetable, which is why we’re able to see this precious bay at a time when many others can’t. “It’s an incredible sense of freedom,” says Rob, who, in 2009, left a stressful IT job in South Africa to start a life out at sea. I ask him if he gets tired of doing this. “Do you ever get tired of breathing? Trust me, it gets better and better every day.”

I see what he means when I pull my snorkel back on and head under the water again. In a matter of seconds, we spot a school of yellow scrawled filefish mercilessly nibbling away at the tentacles of a jellyfish. The crystal-clear water irradiates all their features, from their over exaggerated pouts and mermaid-like tails to the bright blue scribbles on their bodies.

There’s an incredible profusion of sea life here. Further ahead, a handful of yellow and dark blue striped sergeant majors sashay towards us. We spot the long and silvery crocodile needlefish, a juvenile unicorn fish with its fluorescent blue dorsal fin and a pale-yellow titan triggerfish, which, thanks to a black strip across its top lip, looks like it has a moustache. Rob then points out a scorpionfish; I only catch a fleeting glimpse, as the creature is so well camouflaged against the seabed, yet its venomous spines, from which it gets its name, are poised and ready to ward off any predators. We even find a boring giant clam, patterned with almost hypnotic navy and turquoise swirls. Anything but dull, it’s named for its ability to tunnel and embed its entire body into the coral it calls home.

It’s clear to see that Maya Bay’s period of regeneration has had a positive impact. Some sources say that at the time of closing, only 8% of the coral remained — a stark comparison to the 70% of three decades ago. Since 2018, restoration projects by university students and volunteers, and organisations such as Ocean Quest Global and Reef Guardian Thailand, have planted around 20,000 coral fragments to help rebuild the bay’s damaged reefs. The coral regrowth has enticed marine life to return to these waters, Rob tells me, and resulted in a healthier ecosystem.

To avoid history repeating itself, visitor numbers to the bay are now limited by the Thai authorities, swimmers and boats are prohibited from getting too close to shore and travellers can only enter the beach via a new pier built behind the bay. When we’re called back to the boat for breakfast, inspired by what I’ve seen, I ask Rob how we can be more sustainable visitors. “Remember! Love and observe, leave only footprints, take only pictures,” he says. “If you do that, everything will be OK.”

The native inhabitants of Monkey Beach frequently emerge from the bordering forest. Photograph by Anna Jedynak, Getty Images

Life at sea

It’s still only around 6.45am when the Thai national anthem starts playing through the boat’s speaker. Thai co-captain Thanongchai Nacovong, who goes by the nickname Do, is busy — as he seems to be every minute of the day — releasing the anchor and preparing for our departure. Our onboard chef, Ice (real name Kanjarin Promsi), is in her small kitchen, putting the finishing touches to our breakfast: khao tom goong, an aromatic soup of rice, shrimp, spring onions, garlic and coriander, all swimming in a hearty chicken broth. I pour myself a cup of black coffee and sit in the cockpit lounge area, savouring a moment of quiet — knowing that I’ll soon be called upon to help steer the boat towards the mangrove-laden Koh Yao Yai. Helping out during sailing hours isn’t compulsory, but all part of the spirit of sea life. Despite this being a very photogenic part of the world, my phone stays firmly tucked away in my cabin.

It isn’t long before I’m standing at the helm of the boat, a pair of binoculars looped around my neck as I take control of the wheel with Rob and Do by my side. Near the helm is Do’s Buddha necklace, wedding ring and prayer beads — as well as a big bottle of mildly spiced Thai tea. Do, who’s 36 years old, has been sailing since he was 18 and spends more than a third of the year on the water. He loves it so much, he tells me with a happy look, that this will be his life until he retires.

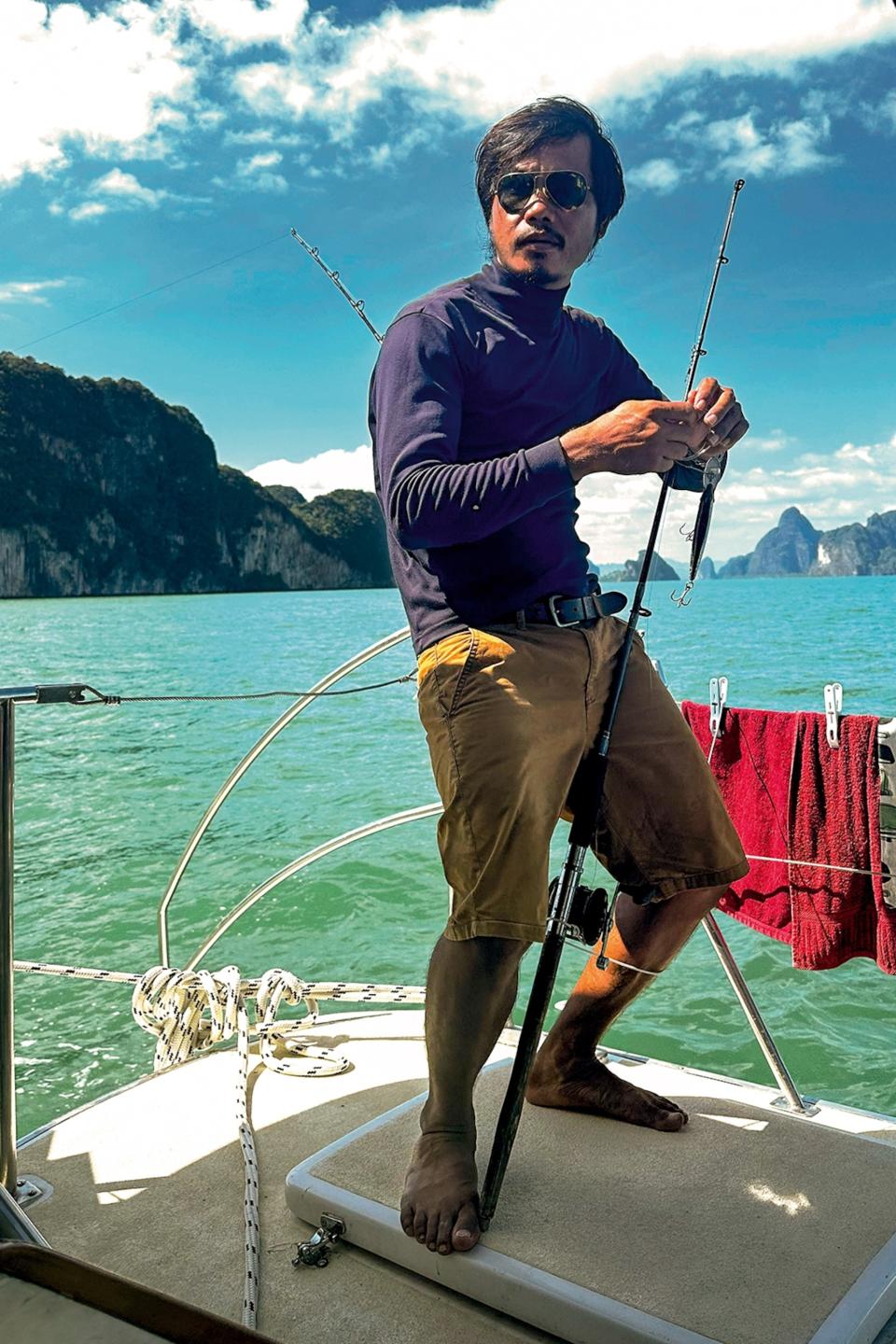

Captain Do is well practiced in baiting up a line to fish for squid. Photograph by Farida Zeynalova

We head northwest to Koh Yao Yai, a peaceful island home to a handful of palm tree-lined beaches. The landscape has stayed largely the same since we left Phuket four days ago. Rob explains that the topography of this region was caused by a geographical explosion “from here all the way to Myanmar” that happened millions of years ago.

Rob clocks the knots slowly increasing as we head north, thumping the helm excitedly as the wind increases our speed. In front of the boat, he points out white caps — or ‘sea horses’ as Rob endearingly calls them — small, white breaking waves that signal rising winds.

Just before lunch, we reach Ao Son Bay in the north west of Koh Yao Yai — Rob says this is a great spot for more snorkelling before we sail on to Phuket. He isn’t wrong — when we slip into the calm waters, it doesn’t take us long to find everything from sea cucumbers and blue and yellow starfish to blue parrotfish and vivid green algae clinging onto corals.

Phranang Cave Beach on the tip of the Railay Peninsula in Krabi is particularly breathtaking at sunset. Photograph by Chris Mouyiaris, AWL Images

Back on board, I take an hour or so to myself and relax by the trampoline net hooked to the front of the boat. I’m almost asleep, when a high-pitched racket snaps me out of my stupor. Ice darts out of the kitchen screaming, a knife in one hand while carefully carrying a bowl of homemade mango ice cream in the other. One of my fellow guests has spotted a Bryde’s whale breaching in between the emerald waters of Koh Yao Yai and our next stop, the privately owned Koh Mai Thon.

It’s in the distance off to the starboard side, leaving a trail of silky smooth water in its wake. The look of glee on Ice’s face is priceless — no wonder, as I soon learn this is only the fourth time in the 10 years she’s been the boat’s cook that she’s spotted a whale. We follow the huge creature at a safe distance for about 10 minutes before changing course.

Later that day, we set sail back towards Phuket, dropping anchor at the tree-clothed Koh Mai Thon’s eponymous beach for a spot of paddleboarding. We’re one of only four vessels here. From the boat, you can’t see the beach for the trees, but once we paddle closer, its solitary wooden swing, white sand and washed-up corals reveal themselves in stages. It’s no wonder that back in the 1930s, American businessman Clinton Washburn fell for its idyllic charms, bought the island and started offering it to newlyweds for their postnuptial getaways. After that, one of Life magazine’s editors simply dubbed it ‘Honeymoon Island’, which it’s still known as today.

After dinner, back on the boat, the sun starts to set. It’s the most mesmerising sunset I’ve ever seen — a soft, powdery amalgamation of yellows, oranges and reds. It’s soundtracked only by the calming chirrups of the birds that nest among the surrounding limestone rocks. Despite having seen this countless times, Rob turns to me and says, “Now do you see why I love my job so much? What a sight!” He’s saved the best until last, it seems.

Published in the Cruise guide, available with the Jan/Feb 2025 issue of National Geographic Traveller (UK).

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) magazine click here. (Available in select countries only).

Read the full article here