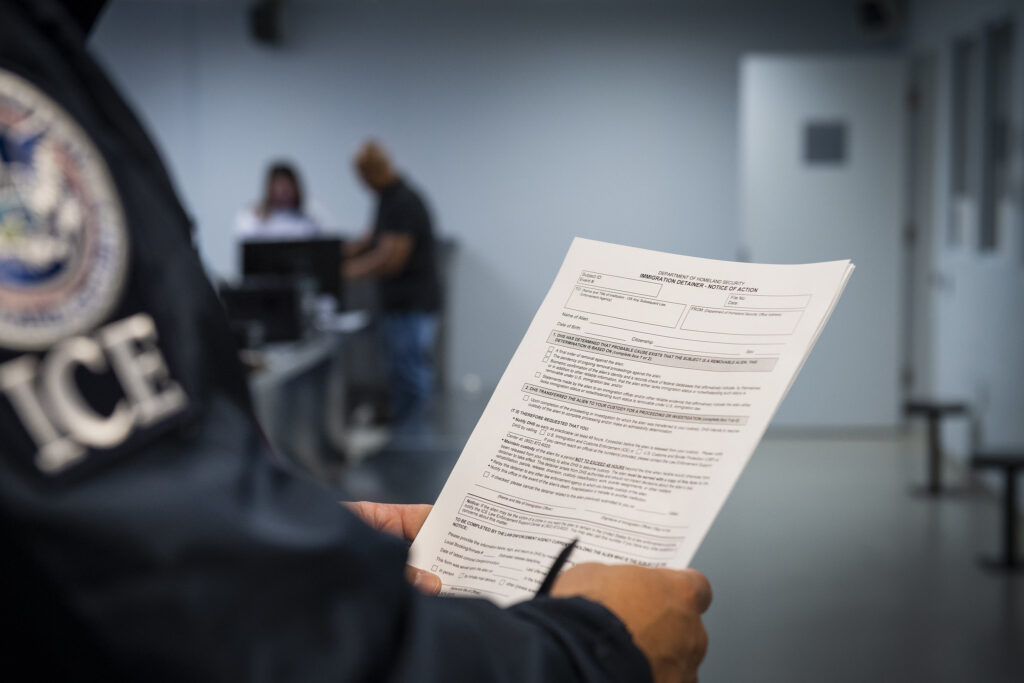

(Photo: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement)

Douglas County Sheriff Daniel Coverley on Wednesday stood by his decision to participate in Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s controversial 287(g) program, which uses local agencies to carry out immigration enforcement.

“This is just one tool I get to use to get those people who are committing crimes in my community and who I do not want in my community,” he told lawmakers on the Senate Committee on Government Affairs, which requested a presentation about his department’s involvement with ICE. “If they’re not supposed to be there to begin with, then this is a way to remove them.”

Coverley added that “most” of the immigration holds his agency has are on people committing serious crimes.

He told lawmakers that, while immigration is primarily the responsibility of the federal government, he believes local law enforcement agencies “have a role to play.”

Douglas County Sheriff’s Office opted into what’s known as a “warrant service officer” agreement, one of three types of agreements that fall under 287(g). The agreement allows local law enforcement officers to help with investigations of migrants already arrested and booked into their local jails, and it allows them to execute civil immigration warrants within their jails.

Coverley emphasized that location restriction, noting that officers are not going out into the community and profiling people based on their ethnicity, nor are they asking victims of crime or witnesses their immigration status.

“The only time this comes into play is when you’ve been arrested and charged with a crime and are booked into our jail,” he said.

Still, the agreement represents the agency being willing to take a more participatory role than what is current practice.

Douglas County Sheriff’s Office already informs ICE whenever someone foreign born is booked in their jail, according to Coverley.

“It is up to them whether or not they put a hold on them or what they want done,” he added.

The new agreement standardizes the process, the office has said.

Douglas County, whose county seat of Minden is about 15 miles south of Carson City, has a population of nearly 50,000, of whom about 80% are white and 13% Hispanic.

Coverley told lawmakers Douglas County Sheriff’s Office had 20 people who ICE requested holds or “detainers” on last year. Of those people, nine were picked up by ICE and five had their detainers removed by ICE, indicating the federal authorities did not want to pick them up. Four people were transferred to prison for local charges and two were transferred to other jurisdictions. The ICE detainers would go with the prisoner to those other facilities.

In 2023, the agency had 14 ICE detainers. Of those, six were picked up by ICE, five were transferred to prison as a result of their local charges, and three had their detainers removed by ICE.

Coverley told lawmakers the new 287(g) program isn’t in effect yet “because we haven’t had the training.”

That training, which will be completed online, is expected to take place within “the next month or so” and will involve five of his department’s officers working within the Douglas County Jail.

The training will tell officers “how (they) are to determine their immigration status and what to do from that point,” said Coverley.

“There’s really no way to screw this up,” he told lawmakers. “We book somebody in. We call ICE and say ‘Hey, we think this guy or person is possibly here illegally. Do you want to do anything?’ They say ‘no, we do not’ or they say ‘yes, we do.’ That’s all it is. We’re not violating anybody’s rights or anything. We’re just asking questions based on what we think may be a possibility.”

Douglas County Sheriff’s Office is one of two law enforcement agencies in Nevada listed as participating in ICE’s 287(g) warrant service officer program. The other is Mineral County Sheriff’s Office, which signed an agreement in mid-February, according to an ICE spreadsheet listing all participating agencies.

Mineral County Sheriff’s Office is also listed as having a pending application for participation in what’s known as the task force program, which involves local law enforcement conducting immigration investigations and enforcement in the community.

Task force agreements with ICE were discontinued in 2012 during the Obama administration after a 2011 Department of Justice investigation found widespread racial profiling and other discrimination against Latinos in an Arizona task force. The Trump administration, as part of its aggressive mass deportation plans, has reestablished the program. More than 140 local law enforcement agencies across the country are now listed by ICE as participating.

In February, Douglas County Sheriff’s Office was listed by ICE as a participant of the 287(g) task force program, but days after media coverage about the agreement issued a statement saying it had not signed onto that program.

Coverley acknowledged the issue Wednesday, telling lawmakers “there was some confusion.”

“Initially an agreement was signed with ICE for the task force officer” program, he acknowledged. “That has since been rescinded and corrected. There was some confusion on my part and on the information we got from ICE.”

He did not elaborate further.

The task force component of ICE’s 287(g) program is the most controversial, but migrant rights advocates warn that any type of participatory agreement between local law enforcement and the federal agency will have a chilling effect. Studies have suggested immigrant populations are significantly less likely to report crimes if they know law enforcement works with ICE.

When asked on Wednesday if the relationship between the Douglas County Sheriff’s Office and ICE may change over time, Coverley responded that is “always a possibility.”

“Everything is driven by who’s in the White House,” he said. “The immigration activity and involvement with local law enforcement has changed since the last president to the president we have now and that could change again in another four years.”

Stateline’s Tim Henderson contributed to this article.

Read the full article here