What the ADL’s origins can tell us about what’s holding it back now

Over a hundred years ago a lawyer stopped by a Chicago vaudeville theater to see a show. The ethnic comedy on display offended him so much that he helped create the ADL.

Both the ADL and antisemites like Candace Owens like to link the organization to the Leo Frank case in which a Jewish man in the South who was lynched after being falsely accused of the murder of a young girl, to make the ADL seem more important.

But the ADL actually had its origins in the B’nai Brith’s ‘National Caricature Committee’ and preceding organizations such as the ‘Chicago Anti Stage-Jew Ridicule Committee’ whose mission was to fight ‘ethnic comedy’ featuring Jews.

Often being performed by Jews.

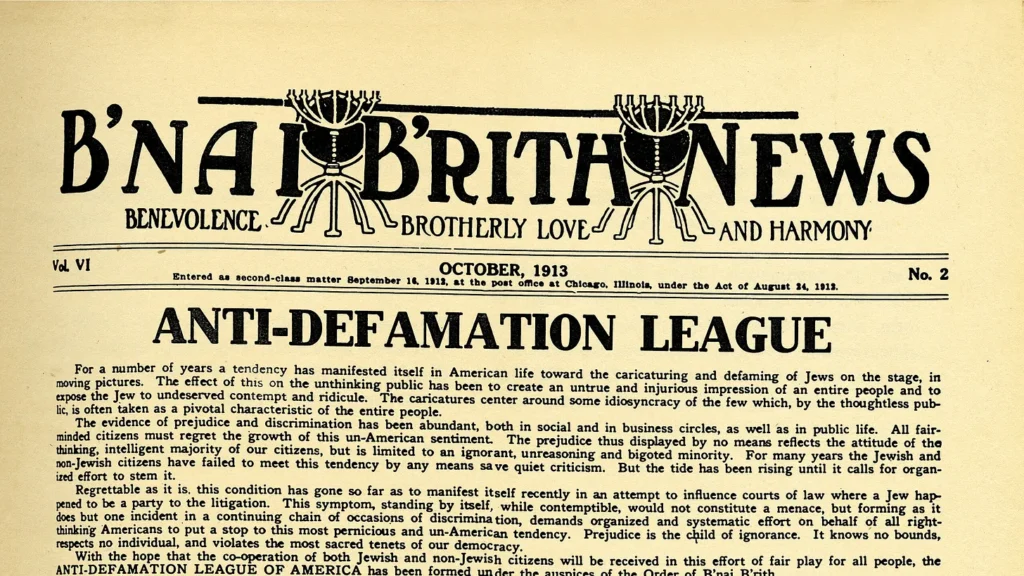

The ADL was not founded as a civil rights organization, let alone an anti-lynching group, but, as an anti-defamation group. Hence the name the ‘Anti-Defamation League’. Its founding charter began by complaining that “a tendency has manifested itself in American life toward the caricaturing and defaming of Jews on the stage” and declared that the “immediate object of the League is to stop…the defamation.”

In the 1900s and 1910s, vaudeville was booming, and successful ‘comedians’ could record their own phonograph records, cartoons were also taking off and silent movies added another form of entertainment. And about the easiest way to get laughs was with ethnic comedy: Germans, the Irish, blacks, Swedes, Italians and Jews were among the many stereotypes to appear on stage.

While we tend to take free speech, including offensive speech, for granted, this was an era where multiple censorship boards, local ones like those in major cities, and ‘voluntary’ national ones, along with local and federal law enforcement, not to mention church groups, could decide whether movies would be released and whether theaters would be allowed to put on a show.

Catholics, the Irish, Germans and Jews deployed pressure groups to get the theaters to stop demeaning them. The NAACP had been at it well before the B’nai Brith launched the ‘National Caricature Committee’ at the initiative of Sigmund Livingston, a member of the German Jewish lodge, who saw an offensive show in Chicago, and Adolf Kraus, a B’nai Brith leader trying to take the local Chicago efforts of the ‘Chicago Anti Stage-Jew Ridicule Committee’ nationwide.

The ‘Chicago Anti Stage-Jew Ridicule Committee’ was not even the most awkwardly worded ethnic comedy pressure group name, that honor likely went to the elongated ‘Society for the Prevention of Ridiculous and Pervasive Misrepresentation of the Irish Character’. The ‘National Caricature Committee’ streamlined the name and the ‘Anti-Defamation League’ streamlined it further. Today the ADL and the NAACP prefer their initials over their awkward full names.

But the much more awkward thing about the ADL was how much of its focus was spent on ‘shande’ politics, policing the wrong kind of Jewish people who were seen as causing antisemitism. Much of the material that the ADL and allied groups objected to was coming from Jewish comedians, theater owners and movie studios. While most of the targets are entirely (and probably deservedly) forgotten, they included future mainstream stars like Fanny Brice who was accused of contributing to “the recrudescence and continuance of the spirit of Anti-Semitism in America”.

This reflected the conviction of many of the German Jews who made up the ADL that the real problem came from the Russian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants like Brice. Sigmund Livingston argued that “the Eastern European immigrants caused an anti-Semitic upsurge”.

The ADL claimed to be fighting against antisemitism, but many of its targets were Russian and Eastern European Jewish performers who were practicing a more traditional brand of humor. The next generation of immigrant vaudeville performers cut their teeth on what would become the Borscht Belt and form internationally famous groups like the Three Stooges and the Marx Brothers, the Bud half of Abbott and Costello, and the George Burns half of George and Gracie.

The lazy ethnic stereotype comedy that the ADL objected to mostly disappeared on its own. The vaudeville performers that went on doing ‘Stage Jews’, ‘Stage Irish’ and blackface (the ‘Stage Germans’ vanished around WWI and were rebranded as ‘Stage Swedes’ like El Brendel or like Groucho, entirely dropped his German/Jewish accent) were left behind with the times. The Marx Brothers dropped most of their stage ethnic comedy (with the exception of Chico) and became a universally absurdist surrealist group rather than a collection of ethnic stereotypes.

The Borscht Belt exemplified the difference between the German Jewish approach of the B’nai Brith and the ADL, which campaigned to be allowed into hotels and country clubs that did not accept Jews, and the approach of the new immigrants which was to build their own hotels and resorts that suited them and in the process unknowingly transform American culture.

The ADL was built around the respectability culture of a German Jewish elite. Meanwhile a more scrappy class of immigrants, with little regard for respectability, were building Hollywood, theater, comedy and popular music on their own terms. They accomplished what the ADL’s politely worded letters and occasional public protests over movies, books or plays could not.

What the ADL was actually doing, objecting to negative depictions of Jews, was less significant than what it wasn’t doing. While the ADL would later bill itself as a civil rights group, it proved feckless and useless at dealing with anything more serious than asking for script changes.

Sigmund Livingston, the ADL’s founder, had been a Republican, but Kraus was a player in Democratic Party politics, and by the time FDR was in office, the B’nai Brith leadership tended to be fashionably (but not excessively) liberal. The New Deal’s targeting of Jews in the Shechter Chicken Case, a key Supreme Court case that blocked parts of FDR’s NRA controls, saw little interest from the allegedly Jewish civil rights group. The Shechter’s kosher chicken stores had been handpicked as test subjects because they fit the antisemitic stereotypes the ADL opposed.

But, as usual, it was different when the stereotypes were coming from progressives.

The Shechter brothers were arrested for “competing too hard” and keeping prices “too low.” Jack Magid, a Jewish tailor, was arrested for charging a customer 35 cents, instead of the NRA code of 40 cents. Making Jews the public face of a campaign to ban underselling played into obvious steretypes that Jewish liberals of the day, much as of today, had to ignore.

During the Holocaust, “rescue was not a high-priority item for major American Jewish organizations, or their leaders, during the war …the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith in these years concerned itself exclusively with domestic matters.” After Pearl Harbor, the ADL’s director appeared to be more worried about the domestic effect of the coming war, concerned that “there will be hundreds of thousands of bereaved families, a substantial part of whom have been conditioned to the belief that this is a Jewish war.”

This was respectability politics at its finest.

By the 1960s that meant much of the ADL’s efforts had been harnessed to liberal projects like civil rights. The rebirth of Israel temporarily banished liberal opponents of Zionism to the margins of the Jewish community where they would remain until more recent times, but the ADL’s support for Israel was fitful and erratic. Much as it had wished that the Russian Jewish immigrants would behave better and embarrass them less, it wished that Israel would do fewer controversial things and cause less awkwardness.

The ADL’s respectability politics tethered it to coalitions, first interfaith ones during the first half of the twentieth century, and then liberal ones in the second half of the century that made it nervous about any Jewish cause, whether it was the Holocaust or Israel.

By the 21st century, the old liberal coalitions had been overrun with leftists, many of which see the ADL as the enemy despite its agreement with them on everything except Israel. The ADL’s various efforts to appease them became doomed by the antisemitic drift of the ‘coalition’ much as its earlier involvement in interfaith coalitions had failed to make meaningful headway during or after WWII.

Over a hundred years later, the ADL is still incapable of addressing antisemitism because it’s too afraid to be something other than a member of a coalition of antisemites. Its origins are revealing because the ADL has always been about external appearances. The B’nai Brith was created out of a need to belong and to feel accepted. The ADL has never been able to go beyond that need for acceptance and is incapable of addressing the issues that really matter.

Daniel Greenfield is a Shillman Journalism Fellow at the David Horowitz Freedom Center. This article previously appeared at the Center’s Front Page Magazine.

Read the full article here