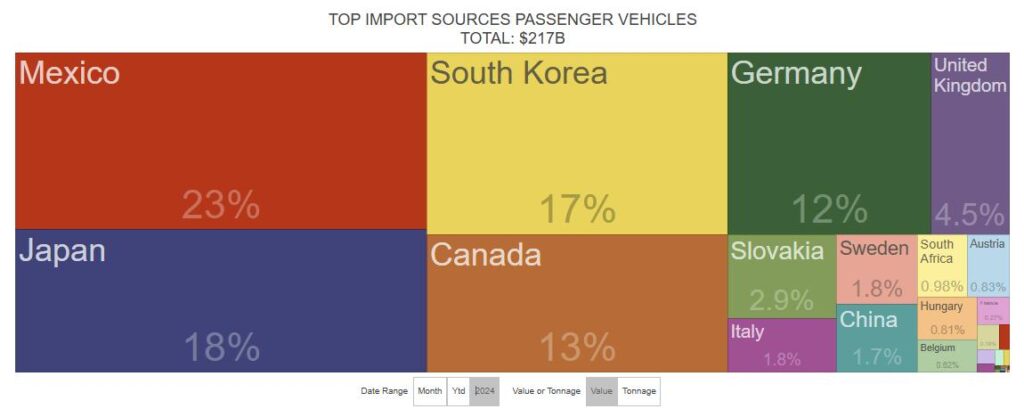

More than 71% of all U.S. passenger vehicle imports came from just four countries last year, with … More

ustradenumbers.comTo the American car-buyer, the U.S. auto industry and its union and nonunion workers: Brace yourselves for the perfect storm that is bearing down on the industry.

- President Trump’s announcement today that he would impose 25% tariffs on all imported cars will impact the No. 1 U.S. import in 2024, valued at $217 billion.

- At the same time, Trump’s tariffs on U.S. imports of steel and aluminum might offer some temporary protection for those U.S. industries. But you can bet those tariffs will drive up the cost of domestically built cars and trucks, an industry that employs multitudes more, as they have in previous tariffs levied against steel and aluminum.

- Trump’s on-again, off-again tariffs of up to 25% on Mexico, the single-largest source of passenger vehicles, pickup trucks and other commercial vehicles, and Canada, the largest supplier of aluminum, will also tie in – since the USMCA partners ship parts across the border, back and forth, during the car-manufacturing process.

- At the same time, Trump’s proposed fees on all Chinese or Chinese-made ships – at least $1 million for each port call – will make vehicles from South Korea, Japan and elsewhere more expensive and further compound the problem. While China now manufactures more than half of all the world’s ships, it is less clear the percentage of the “roll-on, roll-off” or specialized Ro-Ro ships that are used to move cars, though it is certainly a lower percentage.

It’s an odd combination of policy moves for a president looking to increase U.S. manufacturing while at the same time bringing down inflation. My guess is, if implemented – and it’s always a big “if” with President Trump, it would do neither.

An increase in the cost of imported cars – which would be affected by the first and fourth bullet points – cannot be expected to bring down inflation.

The steel and aluminum tariffs, already in place, will make it harder to entice manufacturing to the United States – at least manufacturing involving aluminum and steel – and the on-hold, constantly changing, 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico – will disrupt the heavily coordinated automotive supply chain.

Passenger vehicle exports have been relatively flat in recent years while imports have risen. … More

WorldCityThat is to say, although the focus of this column is the automotive industry, the damage would not be confined to passenger vehicles.

But just the exports and imports related to the U.S. auto industry totaled something like $850 billion last year, or almost 16% of all U.S. trade, according to a rough estimate I did from U.S. Census Bureau data on my company’s site, ustradenumbers.com. Car, trucks and body parts alone accounted for almost $480 billion.

Passenger vehicles were the top U.S. import in 2024, as I mentioned, but also the sixth-ranked export. In addition to the U.S. automakers, most of the world’s large foreign automakers produce cars, almost exclusively in the South.

And it would almost certainly affect those that are connected to the automotive industry.

It would affect the motor vehicle parts industry, if fewer new cars are bought.

It would affect used-car prices, if owners decide to hold on to cars longer. (But maybe boost car parts for those used vehicles?)

Port Laredo ranks first in the nation for the primary category of motor vehicle part imports (above) … More

ustradenumbers.comIt runs the risk of affecting the border crossing in Laredo, Texas, the nation’s No. 1 port and an automotive powerhouse, as well as Eagle Pass, both of which derive large percentages of their annual city budgets from fees paid by cargo-laden trucks crossing their bridges and both of which are in the midst of bridge-expansion projects.

It would, of course, affect Detroit, which gave birth to the U.S. auto industry, including the two primary bridges that serve the area, the Ambassador Bridge and the Port Huron Blue Water Bridge.

The Port of Baltimore led the nation in passenger vehicle imports in 2024, despite the bridge … More

ustradenumbers.comIt will affect the Port of Baltimore, ranked first for passenger vehicle imports, and Brunswick, Ga., ranked first for passenger vehicle exports, as well as the Port of Los Angeles, the Port of Long Beach and the nearby Port of Hueneme, all of which collect fees from ships docking at their ports.

Earlier this year, corporate America stood up and let its concerns be known.

The top executives from Ford, GM and Stellantis were so vexed by Trump’s announcements of 25% tariffs on imports from Mexico and Canada that they made their case in a phone call with the president. At that time, the tariffs were put on hold.

The shipping industry is so vexed by the proposal of charging Chinese or Chinese-manufactured ships – or even the ships of companies with Chinese-manufactured ships on order – they flooded the U.S. Trade Representative’s comment section in advance of the Monday hearing, lamenting its draconian impact. While their concern extends beyond the auto industry, automotive is one of the largest.

And the Federal Reserve is taking note, holding interest rates steady and warning of inflation risks associated with Trump’s tariffs and proposed tariffs, including “reciprocal tariffs” that are supposed to go into effect on April 2.

The combination of 25% tariffs on car imports, tariffs on steel and aluminum imports used in the domestic auto industry as well as many others, fees on Chinese-manufactured ships, and still possibly 25% tariffs on a large swath of Mexican and Canadian imports simply makes no sense.

Read the full article here