House Republicans opted against some of the most dramatic changes they had been considering for Medicaid, the joint federal-state program covering nearly 80 million Americans. But they are plowing forward with other major initiatives that could leave millions without coverage as the GOP starts laying out key provisions of its party-line domestic policy megabill.

The House Energy and Commerce Committee proposal released Sunday night attempts to strike a balance between satiating conservatives’ thirst for deep cuts to the program and placating moderates wary of major coverage losses for low-income Americans.

It does not include the most controversial ideas, including per-capita caps on federal Medicaid payments to states, but it incorporates new mandates that will likely force states to revamp how they finance their programs or cut benefits. The health provisions also include new work requirements that are expected to lead many people to lose coverage, as well as a new cost-sharing requirement for some beneficiaries in the program, not to exceed five percent of a patient’s income.

The Energy and Commerce plan also hits on hot-button social issues — proposing, for instance, to cut federal funding for groups like Planned Parenthood and ban the use of Medicaid dollars for gender-affirming care for youth. It also scales back funding from states that use their own funds to offer coverage for undocumented people.

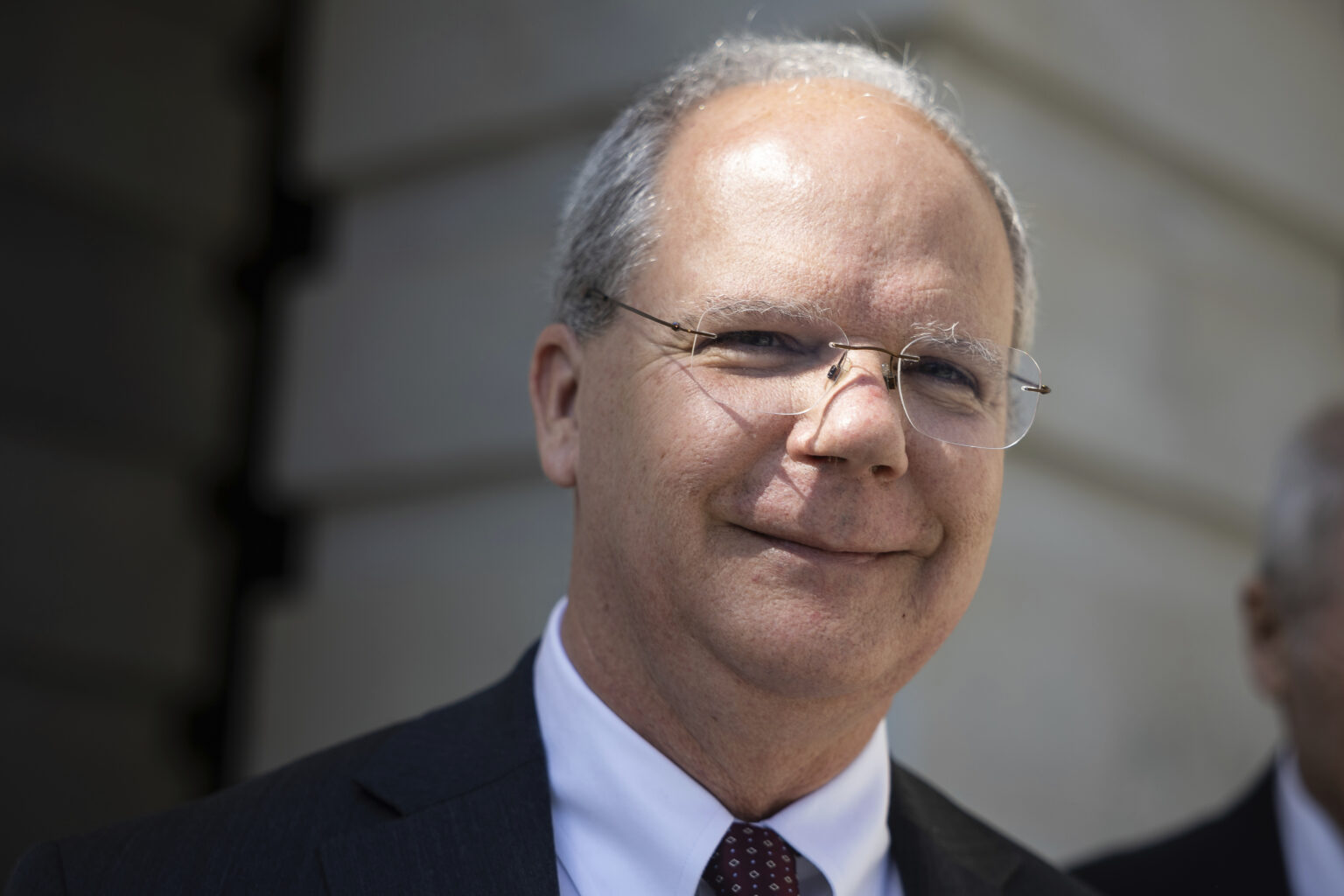

“Democrats will use this as an opportunity to engage in fear-mongering and misrepresent our bill as an attack on Medicaid,” Chair Brett Guthrie (R-Ky.) wrote in a Wall Street Journal op-ed Sunday. “In reality, it preserves and strengthens Medicaid for children, mothers, people with disabilities and the elderly — for whom the program was designed.”

The panel has been tasked with finding $880 billion in savings to help finance a massive portion of the GOP’s party-line package of tax cuts and extensions, border security investments, energy policy and more. Committee Republicans have been under significant pressure to make politically difficult cuts to Medicaid as part of that effort. Guthrie told committee Republicans on a call Sunday that the package will create more than $900 billion in savings, according to two people granted anonymity to describe the private discussion.

The Congressional Budget Office released preliminary estimates requested by Democrats Sunday night found that more than 8.6 million people would go uninsured if the health portions of the package became law, with cuts of at least $715 billion.

Moderate Republicans have been hesitant to make major cuts to the popular safety net program for vulnerable Americans, while fiscal hawks have been angling for transformative “structural” changes. Democrats and many players in the health care industry, including hospitals — which are major employers in many districts — are expected to fiercely oppose the proposal.

“Republican leadership released this bill under cover of night because they don’t want people to know their true intentions,” Rep. Frank Pallone (D-N.J.), the top Energy and Commerce Democrat, said in a statement. “Taking health care away from children and moms, seniors in nursing homes, and people with disabilities to give tax breaks to people who don’t need them is shameful. Democrats have defeated Republican efforts to cut health care before and we can do it again.”

Guthrie worked behind the scenes to placate both moderates and conservatives to get to a deal that both sides can live with, but it remains to be seen whether he and his leadership have in fact landed on a winning strategy. Energy and Commerce is scheduled to meet Tuesday at 2 p.m. to debate and advance the bill.

One of the largest potential sources of savings will come from a policy curbing states’ ability to levy taxes on providers, which could force states to make major changes since the taxes can pay for a state’s share of Medicaid costs. The legislation would freeze state provider taxes at their current rates and prohibit them from establishing any new taxes.

“Provider taxes are an essential mechanism for states to fund their share of the Medicaid program,” said Darbin Wofford, deputy health care director at center-left think tank Third Way. “Weakening provider taxes, as this package does, ties the hands of states and prevents them from addressing their individual needs.”

Conservatives argue that states use the taxes to boost their federal share of Medicaid payments without having to use their own revenue. Doctors and hospitals don’t mind because a state can direct the extra funds back to them, making up for the tax hike.

Every state except for Alaska relies on a provider tax of some form, an analysis from the research firm KFF found. Last year, 32 percent of states’ contributions to Medicaid costs came from other sources such as local government funds and the provider taxes. States cannot levy more than 6 percent of a provider’s income and must tax those on and off Medicaid.

Some states have already warned Washington about what would happen if they can’t levy Medicaid taxes. New Jersey’s Medicaid agency released a model of potential changes back in February and would lead to an estimated $2.5 billion in cuts to federal funding.

Republicans didn’t go as far as they could have gone in going after the taxes, since they don’t peel back current taxes. Provider taxes have also come under scrutiny from top Democrats, including former President Barack Obama, who sought to rein them in in a budget proposal.

The Energy and Commerce draft also would mandate every state to install a work requirement for certain beneficiaries. Able-bodied adults without any dependents would have to work at least 80 hours a month or perform other activities such as community service. It would not apply to pregnant women and only adults from 19 to 64. Tribal members are also exempt as well as those with serious medical conditions.

Congress would leave it up to states to verify compliance with the work requirement.

The bill would also target state-directed payments, which give states more power over provider payments and allow some providers to get reimbursed more in line with what commercial insurers pay them. The goal of the payments is to bolster pay rates for providers and encourage them to enter value-based payment arrangements where doctors are paid based on the quality of care delivered. Conservatives have argued there isn’t enough transparency in the payments.

Here’s what else the package would — and wouldn’t — do:

- Non-health care policies: The package would allow the federal government to auction off wireless spectrum in a move that is expected to generate $88 billion, Guthrie said. It would also claw back Biden-era green energy spending, including climate spending under the Inflation Reduction Act. It would also repeal a pair of Biden administration rules aimed at driving up adoption of electric vehicles.

- Take on some parts of Medicaid expansion: The package would lower the federal share of payments to states that have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act if the state allows undocumented immigrants to get Medicaid coverage. It is illegal for undocumented immigrants to get coverage, but several states take on the full amount of coverage without any federal match.

- Stricter eligibility checks: The legislation would roll back Biden-era rules limiting Medicaid eligibility checks to once annually, allowing them to be made twice a year. Savings would ensue as more are kicked off the rolls.

- Address cuts to doctor pay in Medicare: Doctors have been angling to reverse payment cuts mandated by a formula that lawmakers on both sides of the aisle say doesn’t account for rising costs. The package aims to blunt that.

- Pharmacy benefit manager reform: The package includes an overhaul of the business practices in Medicare and Medicaid of the pharmacy intermediaries, which pharmaceutical companies argue have driven up the cost of prescription drugs. PBMs have argued they help negotiate lower drug prices and the reforms would limit their ability to do so.

- Drug price negotiation: The package would also soften Medicare’s new power to negotiate drug prices under the Inflation Reduction Act for certain drugs. It’s a targeted policy that protects drugs for rare diseases from negotiation if they are approved for multiple conditions instead of if they are approved for just one, as current law allows.

- Trump’s drug pricing proposal: The bill didn’t include a proposal the White House pushed in recent weeks to lower Medicaid drug costs by tying them to the lower prices other nations pay. Trump is expected to sign an executive order to do so in Medicare Monday.

Josh Siegel contributed reporting.

Read the full article here