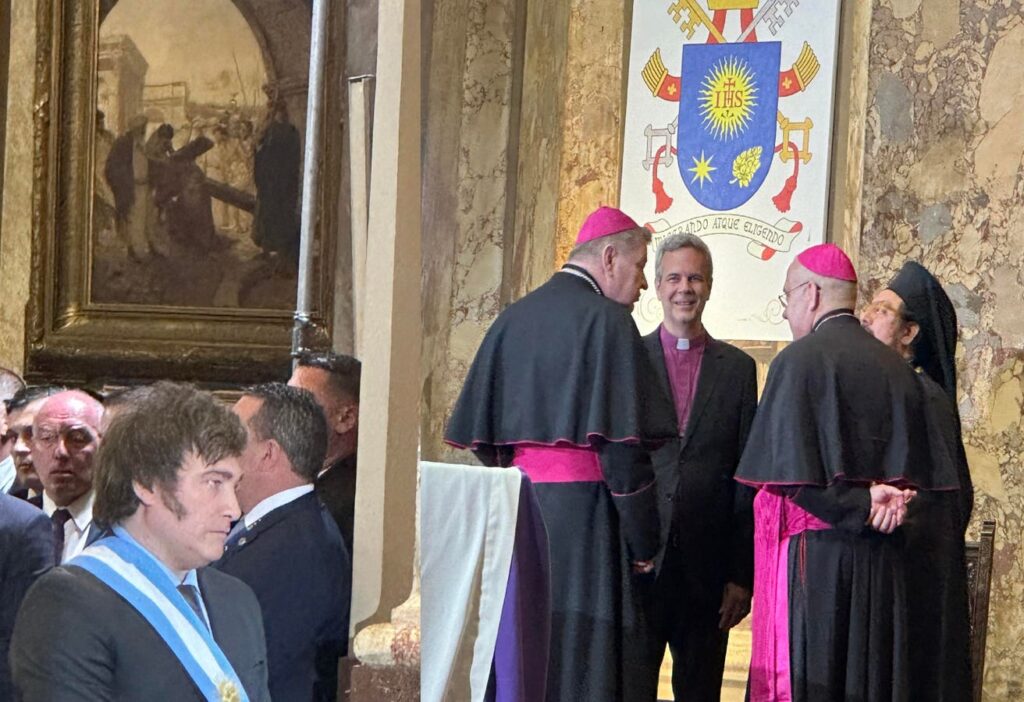

On the inauguration day of his presidency, December 10th, 2023, Javier Milei asked the leaders of … [+]

Javier Milei, the President of Argentina, has set out to change the course of a country that has seen a decline in many measures of well-being in the last eighty years. Today, over forty percent of the population lives in poverty. Students of economic history know that in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Argentina had one of the highest per capita incomes in the world. In 1853, the government adopted a national constitution that promoted a free economy. The following decades saw periods of conflict and internal battles, including an economic crisis in 1890 due to high government spending and easy monetary policy. Yet the country was able to reverse course and return to fiscal normality, and the Argentine “miracle” ensued.

This erstwhile economic freedom owed much to a treaty signed in 1825 between Great Britain and the future nation of Argentina. Though little noted today, the treaty will turn 200 next year, and its principles are well worth recalling, especially in light of Milei’s stated goals for Argentina. These principles extend beyond economic freedom and show how all these liberties are connected. Let us briefly examine the history of the treaty and some of its major tenets.

British forces invaded Buenos Aires in 1806 and 1807, but the locals defeated them. Despite this early animosity, in subsequent years commerce between the “United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata” (now Argentina) and Britain continued to grow. This growth ultimately led to the signing of a treaty on February 2, 1825. The parties agreed to the document “for the security as well as encouragement of such commercial intercourse, and for the maintenance of good understanding between His said Britannic Majesty and the said United Provinces, that the relations now subsisting between them should be regularly acknowledged and confirmed by the signature of a treaty of amity, commerce, and navigation.” Woodbine Parish (later Sir) represented the British King, and Manuel José García represented the provinces of the River Plate.

The first article expresses the parties’ hopes: “There shall be perpetual amity between the dominions and subjects of His Majesty the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata, and their inhabitants.”

The second article of the treaty establishes free trade: “There shall be, between all the territories of His Britannic Majesty in Europe, and the territories of the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata, a reciprocal freedom of Commerce: the inhabitants of the two countries, respectively, shall have liberty freely and securely to come, with their ships and cargoes, to all such places, ports, and rivers, in the territories aforesaid, to which other foreigners are or may be permitted to come, to enter into the same, and to remain and reside in any part of the said territories respectively; also to hire and occupy houses and warehouses for the purposes of their commerce; and, generally, the merchants and traders of each nation, respectively, shall enjoy the most complete protection and security for their commerce; subject always to the laws and statutes of the two countries respectively.”

Knowing that the fine print can sometimes water down the essence of agreements, the framers of the treaty devoted eight articles to a description of how it should be applied. The third article, for instance, stipulates: “His Majesty the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland engages further, that in all his dominions situated out of Europe, the inhabitants of the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata shall have the like liberty of commerce and navigation stipulated for in the preceding article, to the full extent in which the same is permitted at present, or shall be permitted hereafter, to any other nation.” The following articles go into great detail on topics such as port duties, vessels, loading contracts, and other issues where regulations might go against the spirit of the treaty.

Freedom of religion is the essence of Article XII: “The subjects of His Britannic Majesty residing in the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata, shall not be disturbed, persecuted, or annoyed on account of their religion, but they shall have perfect liberty of conscience therein, and to celebrate divine service either within their own private houses, or in their own particular churches or chapels, which they shall be at liberty to build and maintain in convenient places, approved of by the government of the said United Provinces.” It makes freedom of religion a win-win right among cultures, “in the like manner, the citizens of the said United Provinces shall enjoy, within all the dominions of His Britannic Majesty, a perfect and unrestrained liberty of conscience, and of exercising their religion publicly or privately, within their own dwelling-houses, or in the chapels and places of worship appointed for that purpose, agreeably to the system of toleration established in the dominions of his said Majesty.”

The last two articles, important in the consideration of economic freedom as an essential aspect of human freedom, stress private property, and commit Great Britain to help abolish the slave trade. Article XIII states: “It shall be free for the subjects of His Britannic Majesty, residing in the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata, to dispose of their property, of every description, by will or testament, as they may judge fit; and, in the event of any British subject dying without such will or testament in the territories of the said United Provinces, the British consul-general, or, in his absence, his representative, shall have the right to nominate curators to take charge of the property of the deceased, for the benefit of his lawful heirs and creditors, without interference, giving convenient notice thereof to the authorities of the country; and reciprocally.”

In the years that followed the signing of this path-breaking treaty, citizens and immigrants of British ancestry, though remaining a religious minority, founded some of the finest educational, sports, and business institutions in Argentina. Even today, many of these institutions are admired for their governance, their pursuit of excellence, and their openness to the diverse cultures they encountered.

Diana Mondino (right) Argentina’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, International Trade, and Worship, … [+]

Looking at the treaty’s principles from the standpoint of more recent history, we see that Argentines have been much better at protecting religious freedom than freedom of trade. In the Fraser Institute’s 2023 Index of Human Freedom, Argentina scored among the best in religious freedom: 9.49 of 10, just ahead of the United States with 9.48 and the U.K. with 9.45. It was a very different story, though, regarding freedom of international trade — Argentina scored a dismal 3.32, versus the United States with 8.07 and the U.K. with 8.71. The 2023 index’s data is from 2021, the pre-Milei era, so we expect significant improvement in Argentine free trade scores during his tenure.

Looking broadly at the country’s history, we see that religious freedom came side by side with economic freedom in Argentina. Private property to build churches and schools and freedom of trade for prosperity led to Argentine success. Diana Mondino, an economist serving as Argentina’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, International Trade, and Worship, tells me: “Religious freedom, as well as the right to produce and trade freely, were pillars of Argentine growth during the best period of its history.” It is time now to recover economic freedom and continue to celebrate and respect religious liberty.

Read the full article here