Since the Reagan administration in the 1980s, the Heritage Foundation has consistently ranked as the most influential conservative think tank. Now, seven presidents later, in the 20s, Heritage is still shaping conservative thought, as well as national outcomes. And while credit for that achievement goes to many, one figure in particular deserves the most credit: Ed Feulner, who died on July 18 at age 83.

Feulner helped found Heritage back in 1973, and beginning in 1977, he served as its president for a total of nearly four decades. During that time, Heritage traversed from a single townhouse on Capitol Hill to a hulking complex towering over Massachusetts Avenue, just two blocks from the U.S. Senate and the rest of Capitol Hill. It was that proximity—the nearness of conservative ideas to actual political power—that made Heritage so effective. It really could, and did, translate words into deeds.

But that was not the way it always was.

Back in the mid-1960s, when Feulner, a Chicago native, first came to D.C., Republicans were in the deep minority. It was Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in the White House, and his Great Society liberalism was the predominant vision in Congress.

That liberal vision cracked up on the rocks of Vietnam, campus riots, and urban crime; and so, Republicans started winning big. Winning big, electorally, that is, but not tangibly, in terms of actual results. In those days, the forces of liberalism—in the media, in the deep state, and in “RINO” Republicans—were such that the right was thwarted, even clobbered.

Such was the fate of Richard Nixon, the Republican who won the presidency in 1968. That had been a close election, but only because a right-wing populist, Alabama’s renegade Democratic Governor George Wallace, ran as a third party candidate. If Wallace hadn’t run, his 13.5 percent of the vote would have mostly gone to Nixon, not the liberal candidate, Democrat Hubert Humphrey. So, Nixon’s vote-total, a backlash against LBJ’s proto-woke policies, would have been around 57 percent—a landslide. And in fact, the 1972 presidential election, with Wallace not in the arena, was a Nixon landslide. The incumbent Republican president earned almost 61 percent of the vote and carried 49 states.

Yet even after such monster victories, Nixon soon fell into deep trouble. Even when the re-elected president was at high tide, in 1973, the Democrats and their many allies blocked his plan to abolish the worst of the woke back then, the Office of Economic Opportunity, a radical unit within the old Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW, which is now the Department of Health and Human Services).

Even more strikingly, in 1974, the same anti-Nixon forces used Watergate to force the 37th president’s resignation. From massive national defeat to media-driven palace coup in less than two years—now that was a huge comeback and triumph for the left.

This sorry state of affairs led Nixon aide-turned-pundit Pat Buchanan to publish his 1975 book, Conservative Votes, Liberal Victories: Why the Right Has Failed. Buchanan wrote that despite all the conservative election victories of the previous decade, “Conservative influence upon public policy in America has been pitifully small.” He continued: “Conservatives have failed utterly to translate political support and ballot victories into national policy.”

Nixon presidential speech writer Patrick Buchanan speaks at a news briefing in Washington, DC, on May 14, 1974. (AP Photo)

Specifically, Buchanan recalled the 1972 presidential campaign: “Three of the issues upon which the White House rallied the new majority were racial quotas, amnesty, and new taxes.”

And yet, Buchanan continued:

In the next two years, the Department of HEW of the same administration which had sworn eternal hostility toward quotas was imposing them on dozens of college faculties, under the euphemism, “numerical goals and timetables.” And President Nixon’s furniture was not out of the Oval Office sixty days before President Ford had declared a limited amnesty [for Vietnam draft dodgers], and was beseeching his former congressional colleagues to impose a 5-percent surtax upon the very businessmen and middle-class voters who had returned the Republicans to power on a pledge of “no new taxes.”

It was against this dreary backdrop, back in 1973, that Feulner, joined by his close allies, Joe Coors and Paul Weyrich, founded Heritage. Yes, it was a dispiriting time for conservatives, and yet those three amigos were full of spirit—the spirit of spitting in the face of adversity and getting things done.

One of their key insights was that personnel is policy. They realized that a key problem with Nixon’s victories was that there was no conservative bench. Absent a right-tilting talent pool, the people who filled up the Nixon administration—the people in the White House and across the cabinet departments and agencies—were simply not conservatives. So, those non-conservatives were happy to team up with the liberal establishment in Washington, DC, to continue on with liberalism.

Feulner’s idea was to start cranking out effective conservatives who had the credentials to serve in the government. Feulner and his team at Heritage realized that many weighty and worthy books had been written on conservative ideas—Feulner had read most of them and written some of them—and yet the political world was moving too fast for a tome. People on the political firing line needed snappy sentences, not sonorous soliloquies.

So, Feulner built his preferred tool: the two-pager. After all, any good idea, no matter how weighty, can be summed up shortly. Heritage cranked out two-page summaries of issues, written from a right-wing perspective, calling for a right-wing solution. These briefs were put in front of Congressional staffers—Feulner himself had worked on Capitol Hill as a top aide to two Republican Members of Congress—who then served them up to their bosses, the lawmakers. The pithy points, in turn, became soundbites on television and kernels of legislation.

The two-pagers were backed up by scholarship; and the scholars, who tended to be young themselves, were available to chat and consult, albeit with an emphasis on brevity and to-the-pointness. In addition, Heritage staged seminars and brown-bag lunches—anything that could make its ideas user-friendly. This was not lobbying, it was informing. And it all worked, because Feulner and his team at Heritage always knew that good ideas could defeat bad ideas. Sharp presentation was never more important than the basic substance.

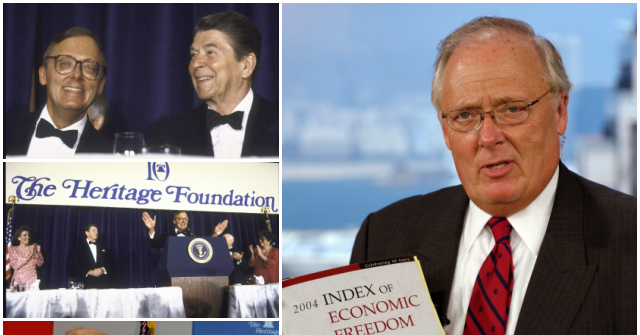

Heritage Foundation President Edwin J. Feulner, Jr. speaks at podium with President Ronald W. Reagan and others watch at a Heritage Foundation function in 1986. (Diana Walker/Getty Images)

President Ronald W. Reagan (right) with Heritage Foundation President Edwin J. Feulner, Jr. during a Heritage Foundation function in 1986. (Diana Walker/Getty Images)

To be sure, other think tanks and idea brokers had their own approaches to influencing policy, and some of them worked too. Yet Heritage was the standout. It created a machine in the 1970s: a conveyor belt of ideas to the legislative branch. And that conveyor carried people in and out of jobs: time on Capitol Hill, time at nearby Heritage, repeat, repeat. And because they had been tested and vetted as they passed through the Heritage mill, they were to be trusted once they got into their government posts–no more conservative votes and liberal victories.

Then, after Feulner’s good friend Ronald Reagan was sworn in as the 40th president in 1981, the conveyor belt extended to the executive branch as well.

The rest is history, as Heritage became a sturdy presence on the right, and a steady influencer of national events. Not everyone loves Heritage, and some hate it. Yet everyone agrees that Heritage has impact, including its many alums now scattered across the Trump administration.

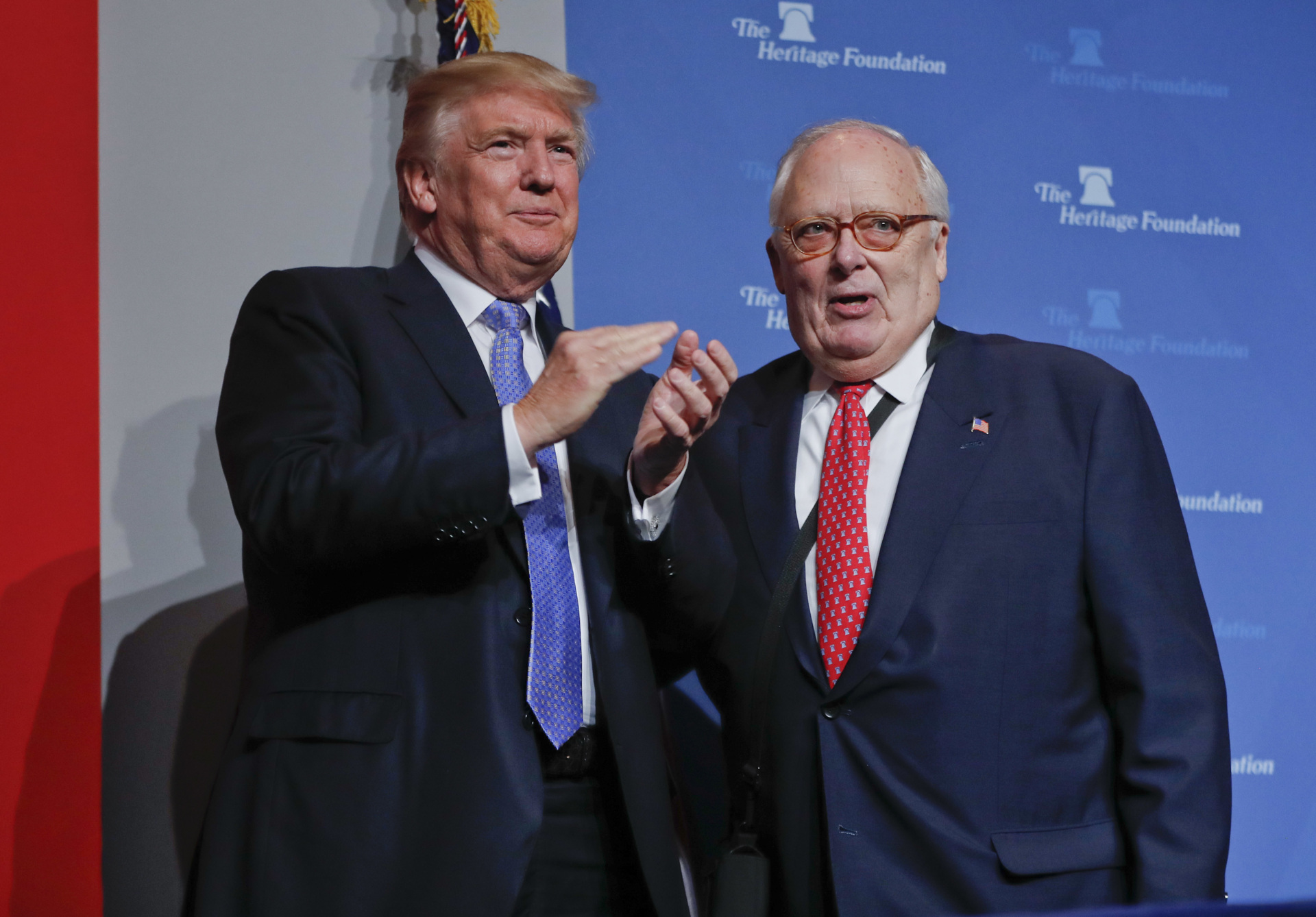

President Donald Trump is introduced by Heritage Foundation founder and president Ed Feulner, right, before speaking at the Heritage Foundation’s annual President’s Club meeting on Oct. 17, 2017, in Washington. (AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)

Feulner had a good idea a half-century ago, and it grew even better as he put his plan into action, year after year, decade after decade. Never himself seeking the spotlight, he was a quiet godfather to the action-oriented right.

That’s his legacy, and quiet as it might seem, behind the scenes, it’s actually epic.

Read the full article here