Sometimes you have to break something in order to fix it.

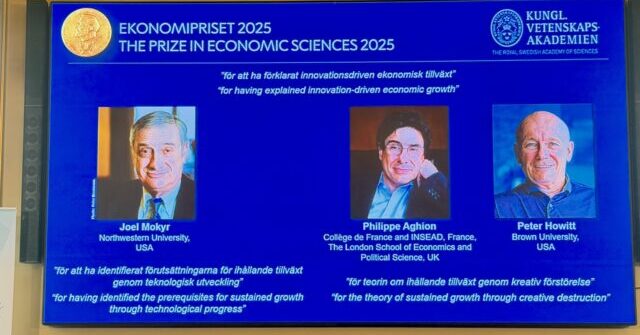

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences on Monday awarded the 2025 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences to Joel Mokyr of Northwestern University, Philippe Aghion of the Collège de France and the London School of Economics, and Peter Howitt of Brown University for groundbreaking research that redefines how innovation and creative destruction drives prosperity—and challenges decades of political orthodoxy on growth, trade, and regulation.

The laureates’ work explains why some societies sustain economic progress while others fall into stagnation. Their findings suggest that political fragmentation and regulatory diversity may be essential for innovation, while some forms of global trade can undermine welfare rather than enhance it, a sharp departure from the economic dogma that prevailed prior to their work.

For most of human history, economic growth was temporary. Societies might experience prosperity after new discoveries, but growth always eventually leveled off. The laureates explain why, for the first time in history, some societies achieved sustained, continuous growth over the past two centuries.

“Economic growth cannot be taken for granted,” said John Hassler, chair of the Nobel committee. “We must preserve the mechanisms that underlie creative destruction so we do not fall back into stagnation.”

Fragmentation as a Growth Engine

Mokyr, 79, used historical evidence to show why the Industrial Revolution began in Europe rather than in other advanced societies like China. In his book A Culture of Growth, he argues that Europe’s division into competing states fostered an environment where innovators could move freely and escape repression.

“In China, the imperial bureaucracy could suppress new ideas everywhere at once,” Mokyr has said. “In Europe, if one ruler rejected your innovations, you could flee to a neighboring state.”

This political fragmentation, paired with a pan-European intellectual network united by Latin, created what Mokyr calls a “market for ideas.” Sovereignty and intellectual freedom created a system that rewarded discovery and tolerated dissent. His work implies that the European Union’s regulatory harmonization or other attempts at building transnational super-states may inadvertently threaten the very conditions that led Europe to become the world’s innovation leader.

Mokyr also demonstrated a crucial distinction between two types of knowledge that explains why some innovations lead to sustained progress while others peter out. He called these “propositional knowledge”—knowing that something works—and “prescriptive knowledge”—understanding why it works.

Before the Industrial Revolution, societies could make important discoveries and inventions. But without understanding the underlying scientific principles, these innovations remained isolated achievements that couldn’t be systematically improved or built upon. Eventually, progress would stall.

What changed during the Enlightenment, Mokyr argues, was that European thinkers began insisting on scientific explanations for practical techniques. This shift allowed each generation to build on previous discoveries rather than simply rediscovering the same things. A blacksmith might know that quenching hot iron in water makes it harder, but understanding the metallurgical principles of heat treatment allows systematic development of new alloys and processes.

This emphasis on understanding causal mechanisms, rather than just accumulating practical knacks, transformed sporadic innovation into the cumulative, self-sustaining technological progress that defines modern economic growth.

Creative Destruction—But Not Offshoring

Aghion, 68, and Howitt, 78, are best known for formalizing the concept of creative destruction, the process by which new technologies displace old ones and drive ongoing growth.

Aghion and Howitt’s 1992 model demonstrated how Schumpeter’s ‘creative destruction’ generates ongoing growth. In their framework, entrepreneurs invest in research to create innovations that make existing products obsolete. Each innovation creates temporary monopoly profits that motivate the next round of innovation, generating a self-perpetuating cycle of progress.

New entrants make older technologies obsolete, but the resulting productivity gains fuel higher living standards. They also identified an “inverted-U” relationship between competition and innovation—too little competition breeds complacency, but too much can deter risk-taking and investment.

But in later work Aghion and colleagues (including 2015 Nobel laureate Angus Deaton) uncovered a deeper truth: what destroys jobs matters as much as the destruction itself. Their 2015 study found that job turnover caused by domestic innovation tends to raise well-being, while job losses caused by offshoring do the opposite. When communities lose firms to foreign production, they experience lasting declines in life satisfaction—even after accounting for unemployment and social insurance.

“The welfare effects of job churn are not symmetric,” the researchers wrote. “When jobs vanish because of innovation, displaced workers can be rehired by more productive firms. When jobs vanish due to offshoring, that mechanism breaks down.”

This distinction challenges the long-standing assumption that all trade liberalization benefits society, suggesting that policymakers must distinguish between innovation-driven and offshoring-driven disruptions.

Together, the laureates’ work suggests that growth thrives on variety and contestability, not on uniformity or uncritical globalization. Mokyr’s insights argue for competitive federalism and regulatory diversity, while Aghion and Howitt’s findings demand trade policies that distinguish between productive and destructive forms of creative destruction.

The Nobel award includes 11 million Swedish kronor (about $1 million), with half going to Mokyr and half shared between Aghion and Howitt.

Read the full article here