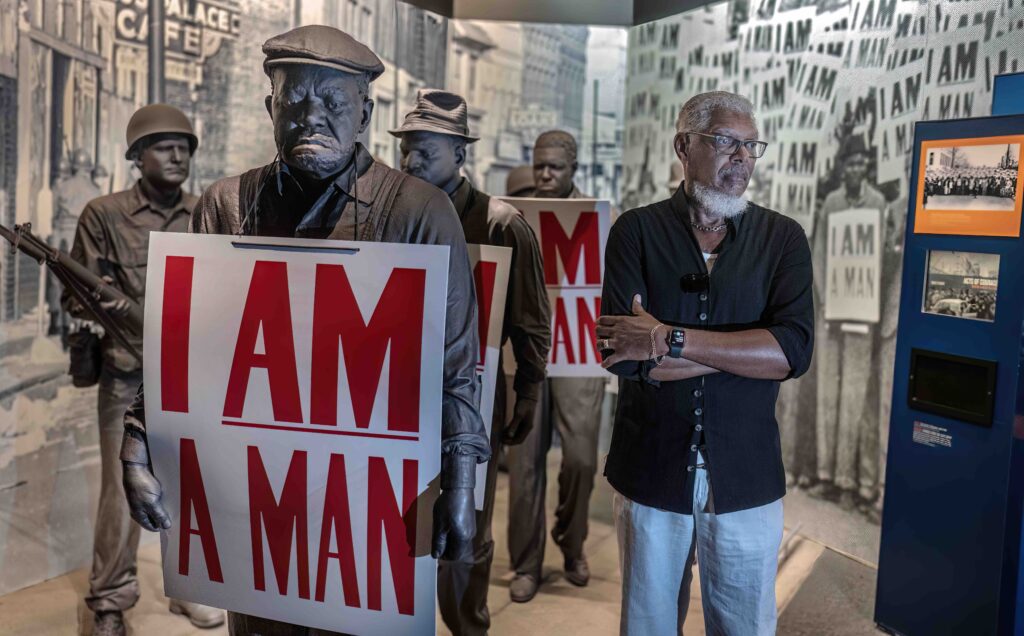

Joe Calhoun lived in the attic of the Clayborn Temple in Memphis for three weeks in 1968 while working on the sanitation workers strike. The strike is commemorated with the I Am a Man Plaza at the now vacant church. (Photo by John Partipilo for the Tennessee Lookout)

MEMPHIS — At the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis one September day, tourists pause solemnly before a group of life-size statues, some crafted in Tennessee National Guard uniforms, others with red and white signs draped around their necks that proclaim, “I Am a Man.”

The visitors are of all ages. Some of the older people doubtless remember the genesis of the “I Am a Man” slogan — the 1968 Memphis sanitation workers strike in which workers wore the signs to point out their humanity in the face of hazardous working conditions.

One man stands apart from the whispering guests. Joe Calhoun needs no videos or displays to remind him of the strike depicted in the museum exhibit.

He lived it.

Calhoun, now 75, assembled the strikers’ signs as a teen during the three-week period he worked adjacent to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil rights icon’s final visit to Memphis before he was assassinated on April 4, 1968.

‘I didn’t understand the scope’

Calhoun moved with his family to Memphis in 1967. His father was a U.S. Air Force officer and was stationed overseas until Calhoun was 15. Life in Memphis was a culture shock.

“I lived in Memphis towards the end of the Jim Crow laws, but the treatment was still the same,” Calhoun said. “There was segregation in stores. Black people could buy clothes but you couldn’t try them on.”

“It was completely foreign to anything I had experienced,” he said. “I came from a very protected and multicultural environment in the military and living out of the country. My background didn’t give me what I needed to arm myself.”

Just months before Calhoun graduated from Melrose High School in Orange Mound, a Black neighborhood on the south side of Memphis, two trash collectors — Echol Cole and Robert Walker — were crushed as they loaded garbage into a malfunctioning truck. The February 1968 incident wasn’t the first time workers had been killed in a similarly gruesome fashion, but Memphis officials still refused to replace the faulty equipment.

The deaths of Cole and Walker were the last straw for their fellow workers, most of whom were Black and worked for low pay in filthy and dangerous conditions, treated more like animals than humans, they would say while on strike.

When a call went out for volunteers to assist with the strike, Calhoun saw an opportunity to get involved, assembling the iconic signs with the phrase on them chosen as a statement of the workers’ humanity.

“The whole civil rights thing was new to me, and I just thought that what was going on was wrong,” Calhoun said. “So when a call went out for high school and college students to help with the strike, I saw an opportunity.”

Calhoun said his parents were concerned about him traveling from their home to the staging site of the strike at the Clayborn Temple near Beale Street in the heart of downtown Memphis. The city was tense, a curfew was imposed and the National Guard deployed to keep order.

For three weeks, Calhoun lived in the church attic, listening as King and other national civil rights leaders, like Bayard Rustin, James Bevel, the Rev. James Lawson and Stokely Carmichael, planned how to get better conditions and higher pay for the sanitation workers.

Joe Calhoun lived in the attic of the Clayborn Temple in Memphis for three weeks in 1968 while working on the sanitation workers strike. The strike is commemorated with the I Am a Man Plaza at the now vacant church. (Photo by John Partipilo for the Tennessee Lookout)

“I was in a meeting with them. I got coffee and cigarettes for Rev. King and others. I was a runner for them,” Calhoun said. “But I didn’t understand the scope of what was happening. You know when you are young, and your teacher tells you to do something, you do it without thinking about the long-term ramifications of what you are doing.”

The 1968 strike wasn’t the first time workers had tried to gain concessions from Memphis. They had been granted a charter for a local union from the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) in 1964 and also went on strike in 1966 but failed. King’s presence in 1968 drew national attention to the workers’ plight, and it was in Memphis the day before his assassination that he gave his last speech, known as “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop.”

Organizers with AFSCME negotiated a deal with Memphis officials to recognize a sanitation workers union, bringing the strike to a close on April 16.

Feet in the movement

King was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel. Just as the Civil Rights Movement didn’t die with him, neither did Calhoun cease his activity.

Shortly after King’s murder, Calhoun traveled to Washington, D.C., to help fulfill King’s plan for a Poor People’s Campaign, living in Resurrection City, the 42-day tent encampment on the National Mall.

In 1969, as a member of the Memphis Invaders, a group that fused the organizing strategies of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the more militant Black Panthers, Calhoun participated in 1969’s Walk Against Fear from Memphis to Little Rock, Arkansas.

Calhoun had met Invaders leader Lance “Sweet Willie Wine” Watson — he later changed his name to Suhkara A. Yahweh — during the sanitation strike. By the time Watson staged the Walk Against Fear, Calhoun was working for VISTA, a federal anti-poverty program, in Forrest City, Arkansas, Watson’s staging point for the march.

During the 135-mile walk, Calhoun and other members of the group faced daily threats of violence from white Arkansans, including, he recalled, from members of the University of Arkansas football team packed into a flatbed truck in Hazen.

Calhoun, left, marched in 1969’s Walk Against Fear with Memphis Invaders leader Lance “Sweet Willie Wine” Watson. (Photo by Ernest Withers, courtesy of Joe Calhoun)

Taking a break and finding a new mission

Around 1970, the Invaders disbanded. Calhoun married in 1974, had children and devoted himself to them and his career as a historian.

His children grew up and moved away.

“After they moved to California, I woke up and thought: now what?” Calhoun said. “Over the last 10 or 12 years, I’ve gotten reinvolved.”

In 2020, after police in Minneapolis killed George Floyd, Calhoun joined a Memphis Black Lives Matters march in protest. He carried a sign that read: “I marched in ‘68. Marching in 2020.” Now, he said, he’s updated the sign.

“I changed 2020 to 2021, then 2022, and now I’m changing it to 2025.

“People ask me what is different about marches today and in the ’60s. Seventy percent of the marchers in Black Lives Matter marches were not of color,” Calhoun said. “Marchers were seeing how people in other parts of the country were treated.”

He has mentored Tennessee state Rep. Justin Pearson, the Memphis Democrat who made national news as one of the Tennessee Three when the Republican-dominated Tennessee House expelled Pearson for leading a gun safety rally on the House floor in 2023.

These days, Calhoun serves as operations manager for The Withers Collection, a museum just around the corner from the Lorraine Motel that houses the work of Black photojournalist Ernest Withers. He documented the Civil Rights Movement, and the museum features photos of the significant figures in the movement — including Calhoun.

“Everything I do is for my grandchildren,” he said. “It may be selfish, but I want them to live in a better world.”

This story was originally published by Tennessee Lookout, which is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Tennessee Lookout maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Holly McCall for questions: [email protected].

Read the full article here