California is moving quickly to protect undocumented immigrant students — attending elementary schools through university campuses — as top officials Monday outlined steps to guide school leaders, inform parents and provide mental health support to anxious families.

This deployment of reassurance and resources at public schools, where every child has a right to an education regardless of immigration status, is designed to counter President-elect Donald Trump, who takes office Jan. 20. Trump has repeatedly vowed to order mass deportations to address what he characterizes as the harms of illegal immigration.

The California pushback on Monday came from Los Angeles Unified School District Supt. Alberto Carvalho on the first day of the spring semester and state Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta.

Carvalho highlighted mandatory upcoming training for employees about what assistance or documentation they cannot or should not provide to federal immigration authorities. The nation’s second-largest school system also will provide information cards to parents listing their rights.

The schools chief also promoted state-funded mental health support for students that will be available online or by phone. It can be arranged in person through a school or online through the district’s “parent portal.”

“These are necessary steps for people who are members of our community, who are tax-paying members of our community, who are students in our environment, who are members of our workforce,” Carvalho said.

Bonta acted in a similar vein, releasing guidance for parents, in part stating that information about citizenship or immigration status is never needed for school enrollment. A second document was prepared to help school districts comply with state law limiting state and local participation in immigration enforcement activities.

“You can be sure that if Trump attacks the rights of our immigrants, I will take action,” Bonta said.

Read more: Trump signals he will deliver on promise to clamp down on illegal immigration

“We’ve been here before,” he said, referring to Trump’s first administration. ” We’re ready to do it again… We’ve been preparing for weeks and for months [for] Trump’s latest plans for mass deportations and arrests, his claims that he’ll deport U.S. citizens and use the military… His plans are inhumane, illogical and fiscally irresponsible.”

The media office for the Trump-Vance transition team did not immediately respond to a request for comment, but Trump has repeatedly blamed immigrants — legal and otherwise — for crime and bad turns in the economy.

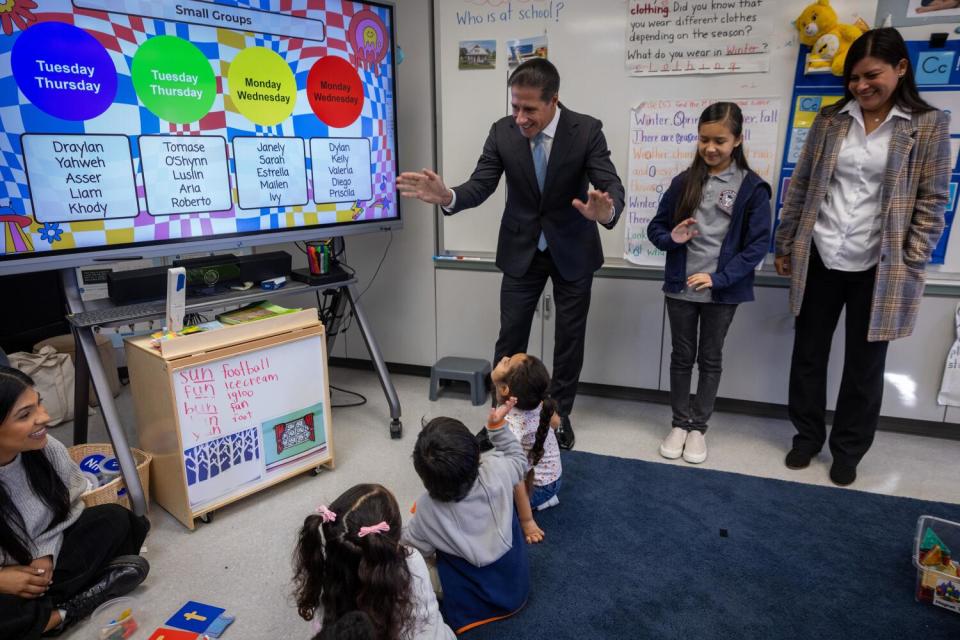

John Mack Elementary School transitional kindergarteners during class on the first day of the school year’s second semester on Monday. (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Undocumented college students fearful

Fears are growing among students and families, including college students who were brought to the U.S. as children, but lack documentation to live here legally.

Jenni Hernandez attends Sacramento State — a campus that welcomes immigrants — located in a sanctuary city in a sanctuary state. Yet because she lives in the country without authorization, the amplified fear she now feels yanks her back, she said, to when she was a 7-year-old and first learned her parents could be deported at any time.

“Where a lot of my peers would have nightmares about monsters under their beds or things like that, I had a genuine fear that one day my parents were just gonna be gone and I would never know what happened,” Hernandez said. Now, she said, “I’m back to that fear.”

“I don’t feel safe anywhere right now.”

Hernandez is one of an estimated 100,000 undocumented college students in California — the most of any state — who are confronting uncertain futures. There are an estimated 408,000 undocumented college students nationwide.

Read more: Top Trump advisor warns California cities not to block immigration enforcement

Some students in college are even grappling with the question of whether they should remain.

“I think it does put into question the idea of pursuing higher education, putting yourself out there post-election, if it’s going to put yourself or your family members in danger,” said Madeleine Villanueva, director of higher education at the California-based nonprofit Immigrants Rising.

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, or FERPA, is a federal law that prohibits colleges from sharing any personally identifiable information from student records without the written permission of the student, according to guidance from the President’s Alliance on Immigration and the American Assn. of College Registrars and Admissions Officers.

But colleges can be required to disclose information without student consent if presented with a court order or subpoena, the law says.]

Model policies, from the state attorney general, suggest giving students an annual notice of what FERPA protects and what type of information may be available through a school directory — and how to opt out of the directory. The guidance advises limiting the collection of information about a student’s immigration status or national origin unless necessary or required by federal law.

It also recommends that colleges adopt policies on who can access different campus facilities, such as libraries, academic buildings and staff- or student-only lounges. According to federal law, immigration enforcement officers would not need a warrant to enter a university quad, but they would need one to access university student housing.

The uncertaintly heightens students’ fears.

“The threats are real and it feels like they’re reinforced almost daily,” said Paulette Granberry Russell, president of the National Assn. of Diversity Officers in Higher Education. “Students are going to worry about whether they can continue their studies, whether their families will be safe. There’s a culture of fear … and we can’t ignore that.”

The University of California has set up a resource page. A statement said the university recognized “uncertainty and anxiety” ahead of inauguration day and welcomed students “regardless of immigration status.”

“We are monitoring the [presidential] transition closely and assessing the potential impacts,” the statement said.

Many public colleges in California offer students and their immediate family members access to free immigration legal services through partnerships with local advocacy groups.

At Cal State Stanislaus, students could usually get an appointment with a lawyer in a matter of days, said Guillermo Metelin Bock, who coordinates support services for undocumented students. But by mid-November, the slots were booked through the end of the year. Students with DACA status are scrambling to apply for renewals before Trump’s inauguration, and those who have green cards — or have family members who do — are petitioning for naturalization, he said.

DACA no longer available

Many of today’s students don’t have a long-term protected status known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). They had to be at least 15 years old to apply for DACA protection from deportation and to gain a work permit. But by the time they were old enough to apply, the program was embroiled in court challenges. It has not accepted any new applicants since 2021. Trump unsuccessfully tried to end DACA during his first term, and could make another run at it.

Trump recently suggested that he would work on a plan to allow Dreamers — people like Hernandez who were brought to the U.S. as children — to stay. In the same interview, however, he offered cold comfort, saying, “I don’t want to be breaking up families, so the only way you don’t break up the family is you keep them together, and you have to send them all back.”

L.A. Unified’s sanctuary efforts

The state does not collect data on the immigration status of younger students, but it is widely believed that their numbers are sizable as well — many are the younger siblings of the college students.

Carvalho recounted a recent conversation with a Garfield High student who proudly wore his Army uniform as a member of that school’s ROTC program.

Read more: Trump said he would revoke birthright citizenship. It hasn’t worked in the past

“He looked as sharp as you could picture any student in his ROTC uniform,” Carvalho said.

In a private conversation following the school event, the student confessed his fears.

“He said, ‘I don’t know what tomorrow would be like for me. I’m wearing this uniform today as a member of the ROTC. I hope to one day join the Army. This is a uniform I want to wear, but my family, myself, we are not here legally, and I fear I don’t know what tomorrow will be like.'”

The elected seven-member Board of Education has joined Carvalho — and directed Carvalho through a series of resolutions and statements — to make L.A. Unified a sanctuary for immigrants as well as for members of LGBTQ+ community, another group that could face potential fallout from the changes in the administration in Washington, D.C.

“This board, this administration, shall not waver from our commitment, our professional and moral responsibility to care for, to protect, to support our students and their families, regardless of their immigration status,” Carvalho said Monday at John Mack Elementary School, south of downtown.

“Secondly, we will use all available resources to us, in partnership with the city and the county, to declare that our schools, our schools are protected ground. We would not allow any law enforcement entity to take any type of immigration action against our students or their families within our care… This is not only about our students or their families. It’s also about our workforce.”

Los Angeles Unified Supt. Alberto Carvalho visits with John Mack Elementary School transitional kindergarteners during class on the first day of the school year’s second semester on Monday. (Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

No protection off campus

Even if schools can be made off limits to immigration enforcement, the student, the employee and the family lose some or perhaps all of that protection when they step off school grounds. Officials also have stressed that it is too early to know what is going to happen.

L.A. Unified will distribute an information card to parents outlining their rights, including the right to keep their children in school. Employees will learn what they need to know to limit the access of immigration agents to campuses. For example, immigration agents do not have to be granted access to a K-12 campus without a warrant. And even some types of warrants would not automatically allow them to enter.

Carvalho is hopeful that agents can be kept off campus entirely: “What would the need be to enforce any type of legal proceeding within the campus that could not be done outside of the school? We don’t believe it’s necessary or appropriate. … We do not expect that any federal entity … should have access to schools to enforce immigration policy period.”

And he would like local and state officials to ensure that the passage to and from school is safe. — and also that parents will be at home to greet their children upon their return from school.

State legislators are exploring ways to extend protections.

Assembly Bill 49, put forward by Al Muratsuchi (D-Rolling Hills Estates) would prohibit school officials and employees from allowing federal immigration agents to enter a campus for any purpose without providing valid identification, a written statement of purpose, a valid judicial warrant and proof of approval from the superintendent of the school district, the superintendent of the county office of education or a designee. And then the agent would be limited to parts of the campus “where pupils are not present.”

Senate Bill 48, from state Sen. Lena Gonzalez (D-Bell Gardens), and backed by state Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, attempts to extend such protections a mile out from campus.

Blume is a Times staff writer. Sanchez is a reporter for the the Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Staff writer Jaweed Kaleem contributed to this report.

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

Read the full article here