Interesting game played by a British investment trust: buying shares of other investment trusts and holding companies at a discount to their liquidating values.

Inthe City of London’s investment trust business, dog eats dog. Thus it is that Daniel Loeb, “activist” investor who shakes up torpid corporate managements, found himself under attack from another activist.

Following a shareholder vote on August 14, Loeb pulled off a contentious merger of his London-listed trust with an offshore insurance company that he also controls. But he does not emerge from the fight unscathed. He had to cough up more cash to dissident shareholders than he wanted to.

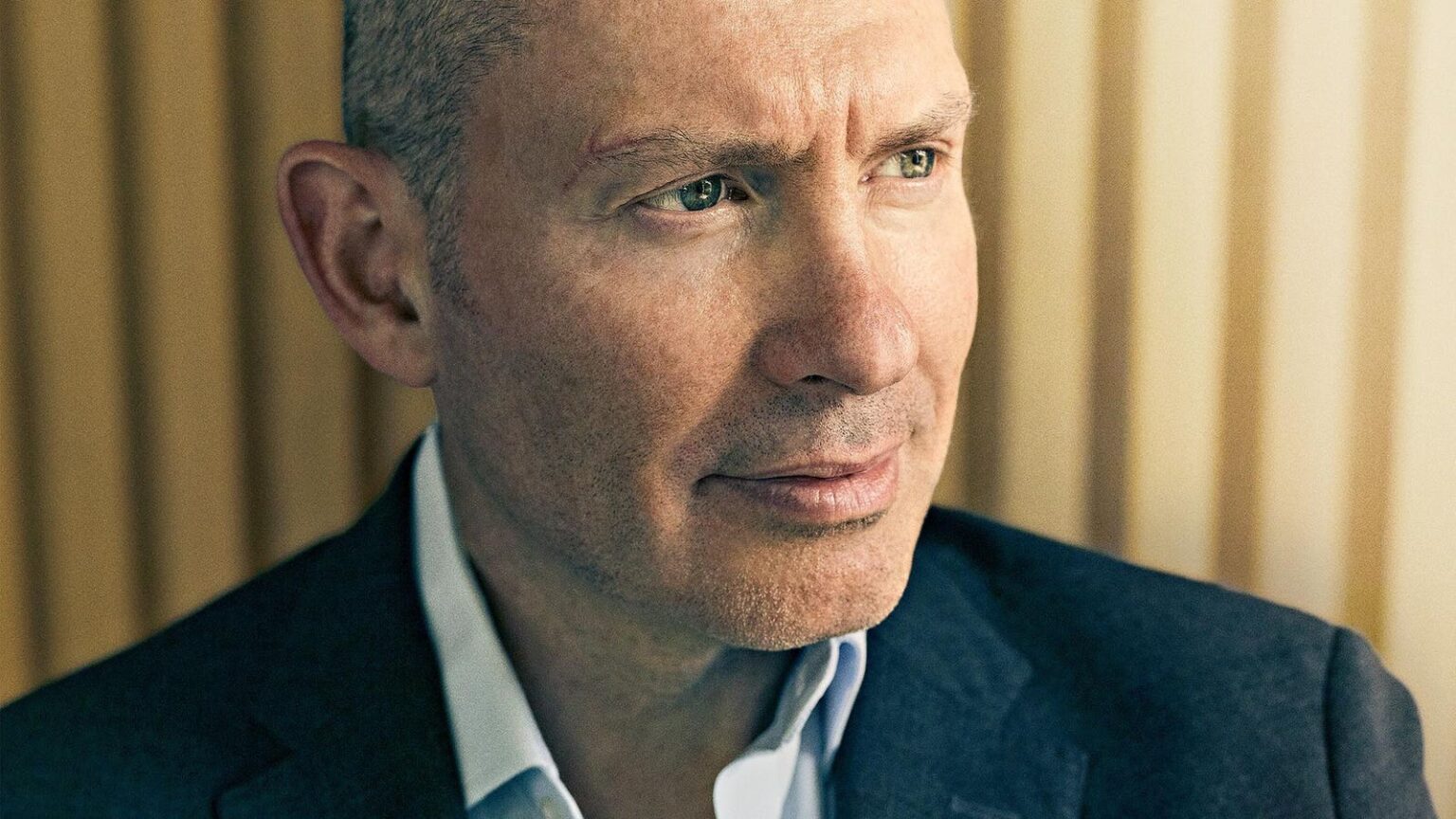

Leader of the dissidents: Joe Bauernfreund, a soft-spoken British money manager who has a curious specialty. He tracks billionaires, or rather, their holding companies. His vehicle is AVI Global Trust, a $1.6 billion U.K. investment company. This venerable closed-end (inception date: 1889) was created to speculate in Africa’s diamond-rich Transvaal region but in recent decades has redefined itself as a value player

Sebastian Nevols for Forbes

AVI buys shares of companies trading at discounts to their liquidating value. A few of these are asset-rich operating businesses, not hard to find in Japan (see “Activism Lite” below). The majority are either other investment companies or holding companies controlled by wealthy families.

Bauernfreund’s targets have included entities controlled by the Agnelli family of Italy (whose wealth comes from Fiat and Ferrari), Leon Black (Apollo), the D’Ieteren family in Belgium (Safelite auto glass), France’s Vincent Bolloré (Vivendi) and Bernard Arnaud (LVMH), Britain’s Keswick family (Jardine Matheson) and the Murdochs (News Corporation).

Most people see News Corp as a media company. AVI characterizes it as a holding company, its juiciest holdings being the Wall Street Journal and a 61% stake in REA, an Australian real estate firm. Bauernfreund says News Corp is trading at a 41% discount to its liquidating value.

Bargain hunting pays off. Over the 40 years since the portfolio manager Asset Value Investors got the contract to manage what was then called British Empire Trust, the trust has delivered an 11.8% compound annual return in pounds, 2.4 percentage points better than that of the ACWI global stock index.

How to play it

By William Baldwin, Investment Strategies Columnist

Asset Value Investors, which manages a trust that started out in African mortgages, has recently been paying a lot more attention to the other side of the globe. Japan is not a bad place to prospect: In its recent seven-year forecast, institutional money manager GMO puts small-company Japanese value stocks ahead of all other asset classes. Adventurous investors whose brokers allow the purchase of overseas closed-end funds should look at AVI Japan Opportunity Trust (expense ratio, 1.5%; five-year average annual return on the net asset value, 14%). A tamer and cheaper option is the U.S.-registered iShares MSCI Japan Small-Cap ETF (expense, 0.5%; five-year annualized return, 7%).

A minority shareholder’s hope is that the insiders controlling a publicly traded entity will, perhaps after some prodding, do something to narrow that discount. They might buy in shares, simplify a complex corporate structure in a way to make the publicly traded portion more attractive or go all-out with a liquidation that erases the discount.

“We can’t force these families to do what they don’t want to do,” Bauernfreund says. “The ones that are interesting to us not only have acted in the interest of their families but haven’t abused minority shareholders.”

Bauernfreund, 53, used to work on the other side of the fence. He started out analyzing real estate for a wealthy family that had a collection of private assets and also a publicly traded property company. In time, the family went entirely private by buying out public investors. Bauernfreund went off to the London Business School for a master’s degree, with a thesis on asset plays. He joined AVI in 2002 and is now its chief investment officer and largest shareholder.

Holding companies can get messy, blending stakes in publicly traded and privately held enterprises. Prime example: the empire presided over by the 73-year-old Vincent Bolloré. Bolloré’s collection of corporations and cross-holdings is dizzyingly complex, but here’s the short version:

Bolloré SE is a conglomerate with ventures in media, logistics and telecom. It owns shares in Universal Music Group, the largest publisher of music, and shares in Vivendi, which was once a water utility but after years of dealmaking has turned into a de facto investment trust. Vivendi owns shares in UMG plus shares of other publicly traded corporations.

Both Bolloré and Vivendi are trading at handsome discounts to their liquidating values, Bauernfreund says. The AVI trust has stakes in each.

Why don’t other people see value? Bauernfreund’s answer: “For many investors, this [kind of company] is just uninvestable, either because they’re lazy or it’s too complex or it doesn’t fit neatly into the way people think about the world.”

Why does a dealmaker tolerate holding companies and their pesky minority shareholders? “Cross shareholdings between various listed and unlisted holding companies in effect allow him to control a greater pool of assets with a limited amount of capital,” Bauernfreund says. “It’s the playbook that many European families have used over the years in order to expand their wealth.”

Another motivation could be tax avoidance. A depressed price on a holding company would presumably be helpful on an estate or wealth tax filing.

In the course of assembling a luxury goods empire and becoming, at times, the wealthiest person on the planet, Bernard Arnault has allowed a stray 2% piece of a holding company called Christian Dior to remain in public hands. Dior, whose sole activity is sitting on shares in widely held LVMH, trades at an 18% discount to the value of its net assets. The AVI trust owns some of Dior’s tiny float; Bauernfreund is betting on an eventual narrowing of the discount, perhaps in a collapse of the holding company structure.

When things work out, a minority shareholder tagging along behind a pooh-bah gets a double-sided gain: The discount narrows at the same time the underlying asset performs well. It is reasonable to bet on the latter, since billionaires didn’t get where they are by making bad investments.

Jackie Enjoy/Getty Images

Activism Lite

The Tokyo market has a wealth of companies with real estate and other assets worth almost as much as their market capitalizations, Joe Bauernfreund says. In effect, you’re getting an operating business for a low multiple, sometimes a zero multiple, of its profits. But outsiders must be patient when nudging management toward an asset sale or share buyback. “Being a shareholder activist against the likes of Dan Loeb has lessons for operating in Japan,” he says, “but we have to approach it very differently. To be an aggressive hostile activist in Japan is to ask for failure.” He expects success with Mitsubishi Logistics and Rohto Pharmaceutical.

Vincent Bolloré started out in the end zone, in 1981 assuming control, from creditor banks, of a financially troubled family enterprise for the sum of one franc and a promise to repay its debts. Now Forbes rates his family’s worth at $10.4 billion. He gets an A+ for performance. What about the discount?

In July France’s Autorité des marchés financiers decreed that Bolloré SE’s entanglement with Vivendi is such that it must offer to buy up all public shares of that entity at a (yet to be determined) fair price. Bolloré is appealing that judgment, but the crackdown was enough to send Vivendi’s share price up 14%.

The contretemps with Loeb ended with a modest win for outside investors. Although based in New York, Loeb set up a London-listed investment trust, Third Point Investors, to gather additional capital. Third Point’s sole asset was a stake in another Loeb entity, an offshore fund that is a private corporation but does disclose a list of its stock positions, recently totaling $7.6 billion.

Falling out of favor, the listed Third Point fund sank to a 31% discount to its net asset value. Loeb decided to merge it with a new entity, a reinsurance company (offshore, of course) that he set up. The new company hasn’t done much but has, per its pitch to investors, a grand plan to coin money by raising capital via the sale of fixed-rate annuities and lending it at higher rates in the mortgage and junk bond markets. As originally proposed, the merger would allow investors in the London fund to get cash for a portion of their shares while being obliged to take shares in the insurance venture for the rest.

AVI, holding shares in the London fund, raised a stink. The change from investment trust to insurer was so radical that shareholders deserved the option to cash out at full asset value, AVI said, and it urged them to vote against the merger. AVI lost the vote but extracted from Loeb an 81% boost in the cash distribution. (A Loeb staffer argues that an independent board blessed the transaction.)

AVI Global has stakes in nine closed-end funds that, like Third Point, trade at a discount to net assets and would generate an instant gain if pushed into liquidation. But AVI Global is itself a closed-end trading at a discount. In 2001, a New York hedge fund grabbed a 16% stake and demanded a seat on the board. The insiders narrowly won a shareholder vote, but the threat of a forced liquidation never went away.

To stay in good favor with shareholders—and with the independent board of the trust, which could fire AVI and hire a new portfolio manager—AVI Global periodically purchases its own shares, keeping the discount to a recent 7%. The sacrificial buys shrink the asset base on which AVI earns a 0.7% annual fee but lessen the risk of a more drastic outcome.

Says a deferential Bauernfreund: “As long as the shareholders are happy with AVI, then the board would probably feel compelled to keep renewing the management agreement.”

Who better than a predator to know how easy it is to become prey?

More from Forbes

Read the full article here