Josie Defreese’s first days as a high school English teacher last year were a little chaotic. Graduating from college just weeks before, Defreese took a job at Beech Grove High School in a diverse Indianapolis suburb, replacing two teachers in a row who had quit.

“I had nothing, no resources,” Defreese said. “I built the curriculum from scratch.”

Though Defreese was the lead teacher in her 11th- and 12th-grade English classes — designing and delivering lessons, grading student work and offering feedback — she was not operating alone. Technically, she was still an apprentice. Her first year in Beech Grove was part of a partnership with local Marian University, a residency program where she’d agreed to be the “teacher of record” at the school while still receiving training and taking courses to earn her master’s degree in teaching.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Novice Indiana teacher Josie Defreese (Josie Defreese)

During her first year, Defreese had both a mentor teacher at the high school plus professors at Marian providing her with ongoing coaching and training.

Marian professors said the design of the program, which began in 2019, was intended to increase the skill set of new teachers by exposing them to the research on learning, but also to get teachers “on their feet” and into classrooms sooner. “We have a teacher shortage,” said Karen Wright, director of residencies and clinical experiences at Klipsch Educators College at Marian. The one-year residency, she said, “gives an opportunity for us to truly partner with our community as well as fully train our candidates.”

It covers the $21,000 tuition for a new teacher’s master’s degree, plus provides a living stipend that ranges from $18,000 to $39,000, depending on teacher qualifications.

Local schools and the university see the arrangement as a win/win: understaffed schools get qualified teachers into classrooms quickly, and new teachers get ongoing coaching and support to hone their skills.

Marian University is one of a growing number of programs overhauling how teachers get trained, moving away from short, uneven practical experiences in classrooms to something more closely resembling a medical residency. Residents do more of the day-to-day work of a licensed teacher but in a more junior position, under the supervision of more experienced teachers.

Apprentice teachers take education courses at night and on weekends while spending their days working directly with students, through tutoring and academic intervention as well as full-time teaching. And unlike traditional programs, apprentice teachers often get paid for their time.

Though the number of residency, apprenticeship and mentorship programs is hard to quantify, experts say the model is gaining popularity not just in university programs, but in non-traditional, alternative certification and “grow-your-own” programs as well.

Teacher Prep Programs See ‘Encouraging’ Growth, New Federal Data Reveal

Program leaders say longer residencies are happening in part due to the profession’s rising demands and changes in the field. Some residency programs focus on specific targets, like equipping teachers with the research— such as on the science of reading — to understand how learning works; others look to create a more diverse workforce or address chronic teacher shortages.

The apprenticeship model has promise, said Suzanne Donovan, executive director of the SERP Institute incubated at the National Research Council. Programs like SERP — the Strategic Education Research Partnership — are looking to add a research element to new teacher residency programs, making early teaching look much more like young doctors training in a research hospital.

“I’m convinced it’s the thing that could make education a system that continuously improves in the way that medicine does,” she said.

New teachers now outnumber any other group

Researchers say improving student teaching is one of the most efficient ways to strengthen student achievement and teacher retention overall. Over the last 30 years, novice and first-year teachers have grown to make up the largest cohort of the workforce, researchers say, outnumbering teachers who’ve worked for five, 10 or any other number of years or more.

Resident teacher Rebecca Auman works one-on-one with a student at Saghalie Middle School in the Federal Way School District in King County, Washington, on Jan. 14, 2025. (Brooke Mattox-Ball/Washington Education Association

According to a 2017 analysis, about 7% of all teachers, or 245,000 out of 3.5 million, are either first-year or novice teachers. In 1987, by contrast, those just entering the field made up 3% of the teacher workforce.

Since new teachers tend to be less effective than experienced ones, and leave in higher numbers, especially the 18% of new teachers that work in high-poverty schools, the student teaching experience becomes critical to success. Teachers in training who have positive student teaching experiences with effective, experienced mentor teachers report feeling more prepared to teach.

The Mentor: One Year, Two Teachers and a Quest in the Bronx to Empower Educators and Students to Think for Themselves

But according to a 2023 report from EdResearch for Action, many state regulations come up short, offering bare minimum requirements ranging in quality. Only 27 states require at least 10 weeks of student teaching under a mentor teacher in the building; even fewer, the report says, mandate a student teacher work full-time during those weeks. Few programs set criteria for what student teaching should include. Mentor teachers often receive no training, and if they are paid at all, receive an average $200 to $250 stipend.

“The frequency and quality of support provided to teacher candidates by mentor teachers and field instructors vary significantly and are often inadequate,” researchers wrote.

Dan Goldhaber (School of Social Work/University of Washington)

“People are not paying enough attention to this issue,” Dan Goldhaber, director of the CALDER Center at the American Institutes for Research, told The 74. “There’s a lot of low-hanging fruit when it comes to making student teaching better.”

Studies have shown, for example, that a more intensive practice period for novice teachers reduced teacher attrition within the first few years.

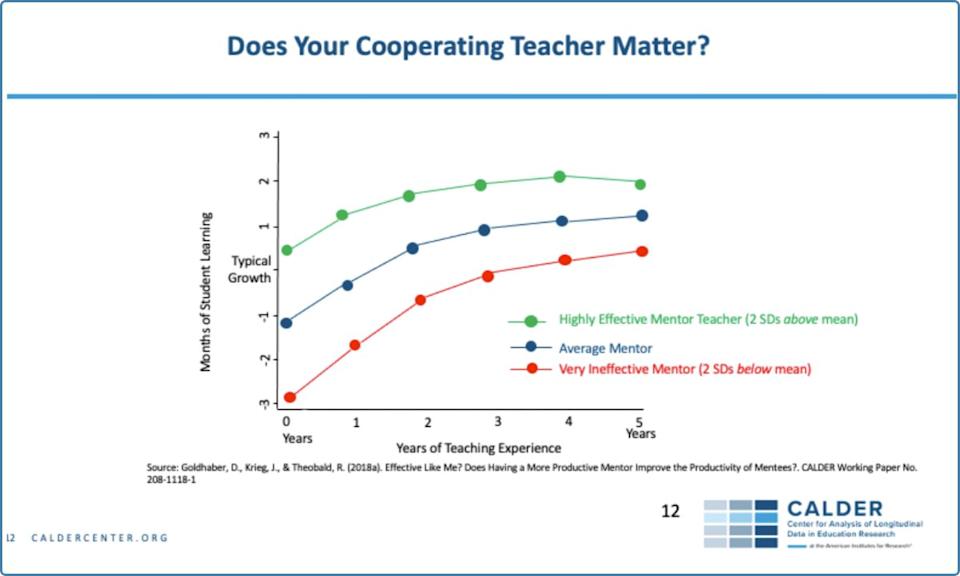

Goldhaber’s own research links mentor teacher quality to how effective new teachers are once they get in front of students. While only about 5% of working teachers volunteer to be mentors, student teachers who do get highly effective mentor teachers perform substantially better once they’re in classrooms.

“If you work with a very effective, two-standard-deviations-above-average mentor teacher, you end up looking almost like a teacher who has two years of teaching experience instead of a novice,” Goldhaber said.

(From Goldhaber, D., Krieg, J., & Theobald, R. (2018a). Effective Like Me? Does Having a More Productive Mentor Improve the Productivity of Mentees?. CALDER Working Paper No. 208-1118-1.)

But several obstacles stand in the way of higher quality training for novices, said Matthew Kraft, an education economist at Brown University. Teacher compensation continues to be a factor, and districts and universities can’t pay for long training periods like in medicine. No such thing exists for educators.

“It’s alluring to characterize teaching as medicine, but we’re not going to have anything close to that until we have something that even approaches medical pay,” Kraft said. “Those things go together. You train many, many years to become a doctor, not only because it’s necessary, but because there are returns to that multi-year investment in your education.”

Getting into the nitty-gritty of teaching

Some new residency and apprenticeship programs are paying more attention to breaking down the steps of teaching. They’re spending more time on research and practical tools in the way new doctors practice the “how” while learning the “why” of treating patients.

When professors overhauled the student teaching program at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, in 2020, school of education dean Douglas Cost said they needed better measures to know whether their clinical teacher training was doing a good job preparing teachers for the classroom. Teacher licensure was the bare minimum.

“Accreditation is an important goal,” Cost said. “But it doesn’t get into the nitty-gritty of teaching. Understanding the science behind learning has given us a real lever to begin thinking about what makes a good teacher.”

Cost and colleagues adopted Learning by Scientific Design, an evidence-based educator curriculum focused on improving student learning. It gives new teachers specific techniques like connecting students’ prior knowledge to what they’re learning, or how to make sure all students are thinking about the material.

“Our professors gave us a template for designing our lesson plans, based on prior knowledge, gaps in knowledge, how to get students up to speed who might have gaps,” said Sarah Cardoza, a former resident and social studies teacher at Wasilla High School in Wasilla, Alaska. “What do you want students to know, and how do you know if they know it? It takes that simple concept and gives you a roadmap for it.”

Cardoza said her first year as a resident teacher, her class had eight students with mandated special education support, three English language learners and several Ukrainian refugees — a lot for a new teacher to handle.

“I appreciated having a plan for how you are going to handle those situations when everybody’s needs are so different,” she said.

In Los Angeles, a Teacher Residency Program Creates Bilingual Teachers

New teachers often don’t have the experience to know how to execute these techniques in a classroom full of students, said Zach Groshell, an independent coach and teacher trainer in Seattle, Washington. Giving them step-by-step specifics — like how to gather students on the rug in an organized way or how to capture attention with a simple arm gesture — might seem basic, but can make the overwhelming first days of teaching much more manageable.

“The generalities of ‘build relationships,’ ‘have a positive classroom climate,’ ‘plan your lessons effectively,’—they’re just too nebulous and vague for new teachers to act on them,” Groshell said. “You need to get more specific.”

A ‘gradual release’ to full teaching responsibility

Traditional student teaching offers new teachers two stark realities: practice lessons in controlled environments, and then full responsibility in a classroom of students. But residency models emphasize “gradual release” to full independence, especially in hard-to-staff areas like special education.

“My first year as a teacher, I cried almost every day,” said Geri Guerrero-Summers, a special education teacher at Mariner High School in Everett, Washington. New teachers went from “you’re going to observe” to “jump right in,” she said. “Student teaching was unpaid. … It’s really a rough type of process in becoming a teacher.”

Members of the Washington Education Association’s teacher residency program participate in Apprentice Lobby Day at the state capitol on Feb. 12, 2025. (Washington Education Association)

Guerrero-Summers now works as a mentor teacher with the Washington Education Association’s residency program, the first teachers’ union to step into training and licensing teachers. Originally funded with federal pandemic relief money, the union residency launched in 2023 and has recently obtained status as a registered apprenticeship program with the U.S. Department of Labor, which comes with an investment of $3.4 million.

Education Dept. Cancels Over $600M in Grants for Teacher Pipeline Programs

“We strive to make sure our residents are classroom ready, no matter where they’re placed,” said Jim Meadows, dean and director of educator career pathways center at WEA.

Future educators begin with 18 weeks working as a paid assistant in special education classrooms, often called a paraeducator, followed by seven weeks of classes, finishing with 36 weeks of clinical rounds, slowly taking over responsibilities as full-time teachers.

Apprentices spend time in a variety of special education settings and age groups. The residency was created to address a specific challenge, an extreme shortage of special education teachers in Washington state. A 2024 state audit found that 1.5% of special ed teachers were unqualified to teach, nearly three times the state average for other types of teachers. Special education vacancies in the state make up more than all other vacancies—including STEM teachers and English language teachers—combined.

Gradual release has been critical for learning the detailed skills of a special educator, said current resident Beck Williams. For example, writing, reading and interpreting Individualized Education Programs, which lay out a student’s classroom supports and accommodations and their learning goals, are covered in coursework but look much different when working with families and young people.

“In special education teacher training, there’s not enough practice with IEPs and parent interaction,” said Williams’ mentor teacher, Angela Salee. Special education teachers often have to play several roles in IEP meetings, advocating for the student’s best interest while explaining accommodations to other teachers, administrators and families.

In Mississippi, where 75% of districts have a teacher shortage, alternative licensure programs like the Mississippi Teacher Corps offer two-year residencies and accompanying master’s degrees to get more teachers up to speed as quickly as possible.

Residents jump right into classrooms and start teaching summer school. They plan lessons and figure out classroom management, all under mentors and supervisors, right away.

“Part of the difficulty of teaching is that you can’t fully prepare someone for the classroom,” said corps director Joseph Sweeney. “So part of it is that experience they need in the classroom. You have to get them on their feet to show them what it’s like.”

Read the full article here