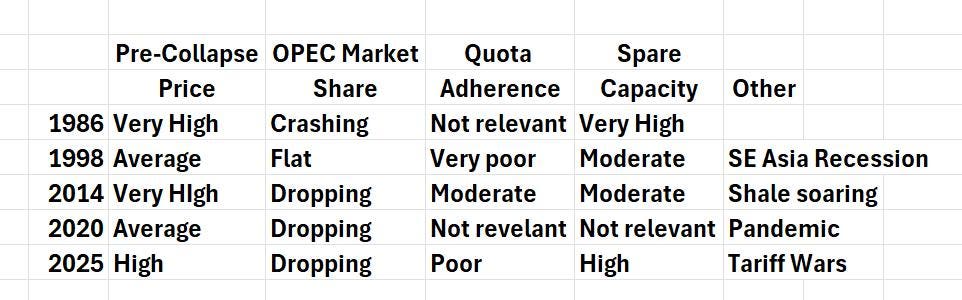

Is the current oil price weakness the beginning of a new price war, and/or heralding a new, lower price level? To summarize, the reasons for past price crashes: 1986, oil price too high; 1998, quota cheating rampant; 2014, shale production soaring; 2020, pandemic, now? The table summarizes the factors leading into the various price drops and shows that pressure on OPEC’s market share and/or quota violations are the primary drivers of price crashes. Both are currently present, though not to the degree seem in previous cases.

Conditions Preceding Oil Price Crashes

The authorOnce upon a time, the oil price was very stable. That was because the Standard Oil Trust was a monopoly and set a price that it would pay for crude. U.S. producers had no choice but to accept them. Rockefeller, who established the Trust, thought volatile prices were bad for the industry (and him). Afterwards, a combination of the Seven Sisters dominance of international oil trade and the Texas Railroad Commission’s quotas on domestic producers kept prices relatively stable.

When OPEC nations gained control over production decisions, a process that began in the late 1960s, they began to set prices on a regular basis after the market stabilized following the 1973 oil crisis. The figure below shows monthly prices paid for imported crude into the United States, which represented the market price. Because OPEC was the source of the marginal barrel and demand for their oil was robust, buyers had to accept the price they set. Except during the 1979/80 Iranian Oil Crisis, monthly prices were relatively stable, but after 1980, only because the Saudis balanced the market.

Price of Imported Crude (nominal $ per barrel)

The author from EIA data.Which set the stage for the first modern price crash in 1986. Although some have attributed the price crash to a Saudi desire (at Reagan’s urging) to hurt the Soviet Union economically, the reality was that the price was too high: demand for OPEC oil dropped by a massive 15 million barrels per day f(mb/d) rom 1980 to 1985, and the Saudis were on the verge of having to buy oil to support the price. They had been acting as the ‘swing producer,’ trying to smooth out demand fluctuations but their production mostly swung down, not up, even as the vast majority of experts insisted that a market turnaround was right around the corner.

OPEC and Saudi Production (tb/d)

The author from Energy Institute dataThe 1998 oil price collapse was very different. For one thing, demand for OPEC oil was relatively flat and Saudi production was a robust 9 mb/d in 1998, suggesting that the price was not significantly above market-clearing levels. However, overproduction by other producers was rampant, spurred by the Venezuelans ss the figure below shows. That country proudly announced that they would no longer obey quotas, and their example led others to follow suit. In response, the Saudis demanded an increase in quota which allowed them to raise production while remaining in compliance. Combined with the Southeast Asian economic downturn, prices collapsed below $10 per barrel, in nominal terms.

Production over quota (tb/d)

The author from EIG data.The other major difference between 1998 and 1986 was that in the former case, prices dropped from historic highs; in the latter, prices were close to historical averages but dropped well below them. And while OPEC market share had not been under pressure going into the price collapse, the 1990s had seen surging production in the North Sea, massive investments in heavy oil in Canada and Venezuela, and expectations (which proved illusory) that gas-to-liquids production would soar. Lower prices meant sharply reduced investment in all non-OPEC production; aided by the booming Chinese economy, OPEC market share rose (figure below).

OPEC Market Share

The author from Energy Institute dataWith Venezuelan production declining after the 2003 national oil company strike and mass dismissals, plus the second Gulf War’s impact on Iraqi production, prices stayed high until the financial collapse of 2008. Prices crashed then but recovered along with demand. The Arab Spring in 2011 and sanctions on Iran meant the loss of another 2.5 mb/d restored prices above the $100 per barrel level, but soaring U.S. shale production began putting renewed pressure on the market. Demand for OPEC oil dropped by 1.7 mb/d in 2014, less than the declines seen in the early 1980s but difficult nonetheless, particularly since there seemed no end in sight to surging U.S. supply.

Thus, as the market weakened in the summer of 2014, the decision was made not to defend the $100+ price level and prices dropped below $30 at one point. Shale production, which had been growing about 1 mb/d per year, went flat and OPEC market share, which had been shrinking, grew once again as the figure showed. The 2020 price collapse was driven primarily by the crashing demand related to the pandemic, but it is noteworthy that OPEC refused to bail out the market without assistance from the Russians.

Now, where do we stand? The table above suggests that the conditions are ripe for another price crash, albeit perhaps a fender-bender. OPEC market share is again under pressure and appears likely to remain so, especially if the alarms about peaking shale oil production prove once again premature. Sanctions on Iran and Russia have assisted OPEC+ in maintaining prices roughly at $70, but that now seems offset by fears of looming recession.

Possibly OPEC+ might decide that the current weakness in prices stems only from recession expectations, encouraging a temporary quota reduction, but the reality is that even before the current chaotic situation, demand for OPEC oil was under growing pressure. Non-OPEC+ supply appears likely to outpace demand growth for the foreseeable future rather as in 1985 and 2014. With members like Iraq, Kazakhstan and the U.A.E. adding to capacity, pressure on the remaining members (translation Saudi Arabia) can only grow.

Aside from the manic fluctuations that White House pronouncements will cause, the big question is whether or not OPEC+ will pause the unwinding of voluntary cuts and even increase them in defense of a $70 price. Given the persistent overproduction by several members and the ongoing decline in demand for OPEC oil, it seems probable that the group (translation Saudi Arabia) will allow a decline in prices, at least until overproduction is reined in. That, combined with tougher sanctions on Iran and/or Russia, could maintain prices at $70, but even in that case, should demand for OPEC oil continue to weaken, expect a new, lower price to balance the market.

Read the full article here