How Corporate Decisions Weakened America’s Economy

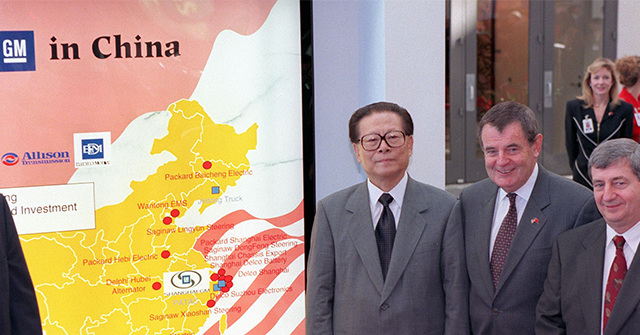

For decades, American companies made a straightforward calculation: They would share their technology with Chinese partners in exchange for access to the world’s largest consumer market and its low-cost labor. General Motors, Intel, and thousands of other firms formed joint ventures that helped their Chinese partners learn advanced manufacturing techniques, chip design, and management practices.

It boosted profits for many of the biggest firms. But a new National Bureau of Economic Research working paper suggests the calculation was a collective mistake—one that left American workers, smaller companies, and the economy as a whole worse off.

The paper—by Jaedo Choi of the University of Texas at Austin, George Cui and Younghun Shim of the International Monetary Fund, and Yongseok Shin of Washington University in St. Louis—argues that the real mistake wasn’t at the company level but at the national level. Each firm weighed its own trade-offs: lower costs and access to Chinese customers against the risk of helping a direct rival. What no one accounted for was how those same deals would strengthen Chinese companies competing against other American firms, from General Motors and Chrysler down to thousands of smaller auto-parts suppliers.

The results echo the famous “China shock” research by David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson, which showed how a surge in Chinese imports reduced jobs and wages in many U.S. communities. But while that earlier work focused on the import side of globalization, this study turns the lens on the investment side: how the choices of American companies themselves helped accelerate China’s rise, with lasting costs for the broader U.S. economy.

What Was Good for General Motors Was Bad for America

The researchers examined what happened to American and Chinese firms between 1999 and 2012, a period when joint ventures proliferated. To separate cause from coincidence, they paired Chinese firms that entered joint ventures with similar firms that didn’t, and they drew on changes in Chinese investment rules to isolate the effects. The pattern was clear: Chinese companies that formed joint ventures grew rapidly, increasing sales by 27 percent within four years. Even Chinese companies that weren’t direct partners benefited, growing faster in industries with more foreign investment.

American firms told a different story. In industries where more joint ventures formed in China, U.S. companies experienced declining sales, employment, investment, and innovation.

Using a detailed economic model, the researchers calculated that if the United States had banned joint ventures starting in 1999, American welfare would be 1.2 percent higher today. That may sound small, but across a $28 trillion economy it amounts to hundreds of billions of dollars. For China, the cost of such a ban would have been far steeper—a 10.3 percent reduction in welfare.

The benefits would not have been evenly distributed in America. Large companies that had formed joint ventures would have lost 22 percent of their profits. But smaller competitors would have gained, and crucially, American workers would have earned nearly three percent higher real wages as companies kept more production at home.

A luxury Cadillac XLR from U.S. auto giant General Motors is on display at a ceremony in the Forbidden City in Beijing, China, on June 7 2004, following General Motors’ announcement of an ambitious expansion in China. (STR/AFP via Getty Images)

A Warning That Went Unheeded

The economists don’t explicitly address a puzzle their findings raise: If joint ventures created such broad harm, why didn’t the government step in? After all, companies aren’t supposed to coordinate with competitors—doing so would likely violate antitrust laws.

The answer involves both economic thinking and political reality. For decades, the Washington consensus held that free capital flows benefited everyone. Restrictions on American investment abroad seemed like the kind of central planning that characterized failing economies, not successful ones. Even economists who worried about trade adjustment costs focused on imports, not on how American companies’ own investment decisions might undermine domestic competitors. The warnings of Patrick J. Buchanan, the conservative columnist whose three presidential bids challenged both parties’ embrace of globalization, went largely unheeded and were often derided by the establishment.

There was also a timing problem. The harm unfolded gradually and was hard to see. By the time the pattern became clear—Chinese firms growing stronger while American competitors and workers struggled—much of the technology had already transferred. The paper shows that restrictions would have been most valuable in 1999, when the technology gap was widest, but that was also when optimism about Chinese integration was at its peak.

Perhaps most importantly, there was no obvious constituency for action. Large corporations forming joint ventures had no interest in restrictions. Smaller competitors being harmed often didn’t understand that joint ventures were part of their problem. And workers, who would have benefited most from restrictions, had no seat at the table when investment policy was made. Many Americans at the time thought of Buchanan’s warnings as unduly pessimistic. Republicans frequently criticized conservative economic nationalists for betraying what they insisted was the optimistic message of Ronald Reagan.

The study suggests that smarter policies than outright bans might have worked even better. If companies had been required to compensate their American competitors for the losses those rivals would suffer from technology transfer, far fewer joint ventures would have formed—and American welfare would be 1.7 percent higher. Similarly, restricting joint ventures only in industries where America had the largest technological lead would have preserved the most important advantages.

America Wakes Up to the Danger of China Ventures

This logic helps explain the bipartisan shift in Washington toward limiting American investment in Chinese technology. The 2022 CHIPS Act, for instance, prohibits companies that receive federal funding from making certain investments in China. What once seemed like protectionism or nationalism now looks closer to common sense.

But the research also carries a warning: These policies made sense two decades ago, when the technology gap was wide. Implementing them now delivers far smaller benefits and may even backfire. The window for using investment restrictions to maintain American technological leadership may be closing.

The deeper issue is collective action. What made sense for each individual company—trading technology for market access—added up to something harmful for the country as a whole. It’s the kind of problem that markets alone rarely solve.

As the United States and China continue to compete in semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and other advanced technologies, the research suggests that policymakers need to think carefully not just about whether to restrict outward investment, but when and in which industries. Getting the timing wrong could make Americans worse off rather than better.

Read the full article here