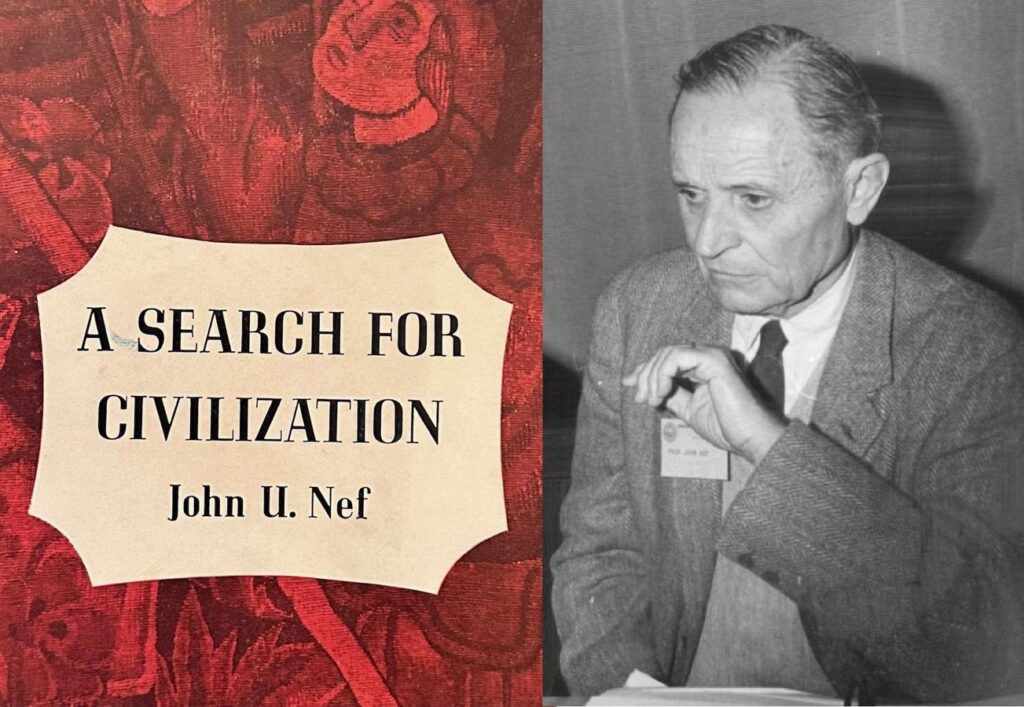

John U. Nef (right) was one of the founders of the Committee on Social Thought, which still carries … [+]

At the beginning of the 1960s, John Nef (1899-1988), chairman of the Committee on Social Thought and professor of economic history at the University of Chicago, wrote a thoughtful book titled A Search for Civilization. For over a decade at Christmastime I have been writing in this space about champions of free society and Christianity. Nef’s 1962 book gives me ample substance for this 2024 contribution.

A historian and social scientist, Nef was one of the driving forces behind the creation of the Committee on Social Thought in 1941. He was a key intellectual figure during its early development, especially in establishing the program’s interdisciplinary nature. He sought to integrate the study of history, economics, and social theory. His vision was to create a space where academics could explore social thought beyond the confines of traditional academic departments. Nef believed in the importance of understanding social systems historically and in a broad intellectual context.

Nef mentored many students and young faculty who participated in the Committee. For instance, Milton and Rose Friedman recalled him in their memoirs as one of their teachers: “John Nef was independently wealthy and had broad interests. He believed that it was desirable to have a group broader in scope than the individual departments.” Friedman added that Nef helped finance the Committee, and he listed Nef among the department’s eminent economists, together with such figures as Henry Schultz, Henry Simons, and Lloyd Mints.

Nef’s intellectual rigor and interdisciplinary approach impacted the program and helped establish the University of Chicago and this Committee as a serious, interdisciplinary intellectual inquiry center. He continued to support the program until his retirement.

After founding the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947, Friedrich A. Hayek joined the University of Chicago in 1950 as a Committee on Social Thought professor. Hayek’s interdisciplinary approach and focus on economics, social theory, and political philosophy aligned perfectly with the Committee’s mission. Although wider in scope and more limited in reach, the Committee on Social Thought can be regarded as a precursor of the Mont Pelerin Society.

As a historian of economic thought, Nef contributed to developing the Committee’s curriculum by emphasizing the importance of history and philosophy in understanding social and economic systems—his intellectual approach combined social science and history, encouraging the holistic study of social structures. Less known, though, are Nef’s views on Christianity.

Nef devoted ninety-three pages, over forty percent of his book A Search for Civilization, to faith and religion. He covers various topics: religion and science, religion and man, religion and wealth, and religion and Christ. His works do not read like the stereotype of a “Chicago Boy,” focusing on economic theory and policy: “The individual who welcomes the light offered by God is essential to the search for civilization. Faith is the only slavery which can deliver a man from slavery.” For Nef, “freedom consists in choosing the right slavery. The true road to freedom is the road of love, and, as we have just said, the only means of loving is to forget oneself. Love is the highest form of slavery.” He saw as a problem the tendency to judge Christian churches, Christian dogmas, and Christ himself according to their contributions to economic prosperity.

Nef elaborates: “Whatever the importance of material progress, and I am disposed to agree that this importance is great, it is a deformation of the Gospel to make such progress the ultimate goal of existence. In doing just that, the holders of this second point of view have encouraged the widespread assumption that material progress is the basis of all progress, including spiritual progress.” Nef rejects this view: “What makes charity the first of the virtues, is that it is the only one which is the same here and in heaven. It is consequently of all the virtues the one that links man most closely to God. So the qualities essential to charity are independent of worldly wealth, and should be a guide to the way in which the wealth is employed.”

Reading Nef, one understands the accolades he received from another scholar who also deserves more recognition, the revered longtime Notre Dame professor Frank O’Malley (1909–1974). O’Malley wrote, “John Nef’s learning has been formed and nourished by Christ’s love and hope. He remains one of the wisest men of our time—and his words should be read by all those responsible for the education of modern people, for the conduct of society, and the proper construction of civilization.” Like Nef, O’Malley believed in integrating literature, philosophy, and theology to explore fundamental questions. Although a professor of English, he was also associate editor of The Review of Politics.

On valuing the contribution of the Christian faith to modern civilization and progress, Nef directs his readers to Alexis de Tocqueville, especially his letters to Gobineau. Arthur de Gobineau (1816-1882) was a champion of the Enlightenment whose analyses Tocqueville found insufficient: “To me it is Christianity that seems to have accomplished the revolution – you may prefer the word change – in all the ideas that concern duties and rights; ideas which, after all, are the basic matter of all moral knowledge.” Nef, as a good historian of thought, did not neglect the many sources besides the Enlightenment that led to the jump in economic prosperity. He writes, “Economic individualism, stimulating to modern economic progress, had many sources. The origins of the industrialized world in men’s minds became compelling, at the end of the sixteenth and in the early seventeenth century, through the scientific revolution and the new technological problems that were raised independently of it at much the same time.”

Although a Christian, Nef hoped that the Committee he helped create and fund would reach all who, independently of their faith, would engage in civilized discourse on the important questions of the day. As an economist privileged to spend quality time with both, I have mentioned Friedman and Hayek; Nef’s Committee, however, had influence far beyond economics. Some of the most famous intellectuals who benefited and enriched the Committee’s discussions are Leo Strauss (1899–1973), Hannah Arendt (1906-1975), Allan Bloom (1930-1992), and Saul Bellow (1915-2005): political philosophers, theorists, novelists, and a classicist.

F.A. Hayek, Allan Bloom, Hannah Arendt, and Saul Bellow, were some of the leading intellectuals who … [+]

John Nef, who died on Christmas day 1988, left us with a question, and I think I know his answer: “The capital question is whether men and women generally are not better than they would otherwise be because of a knowledge of the ethical principles nourished by the Christian faith, which Christian churches have done so much to preserve and to renew for almost twenty centuries.”

Read the full article here