The U.S. Department of Energy announced this week that it has made an initial selection of 11 projects to develop high-tech nuclear test reactors, part of the Trump administration’s ambitious plans to rebuild a domestic nuclear supply chain and quadruple U.S. nuclear energy output by 2050.

Part of Trump’s plan includes re-shoring uranium enrichment, an industry that is now dominated by foreign competitors. The first signs of an attempt to bring this critical industry back to the U.S. were seen earlier this month, with the announcement of a new enrichment facility in Kentucky.

The United States invented uranium enrichment and dominated the global nuclear fuel market until the 1980s. But decades of U.S. underinvestment — coupled with unfair competition from foreign, state-owned companies that benefit from subsidies and trade protections — has left the U.S. without a large-scale uranium enrichment capacity to meet commercial and national security needs.

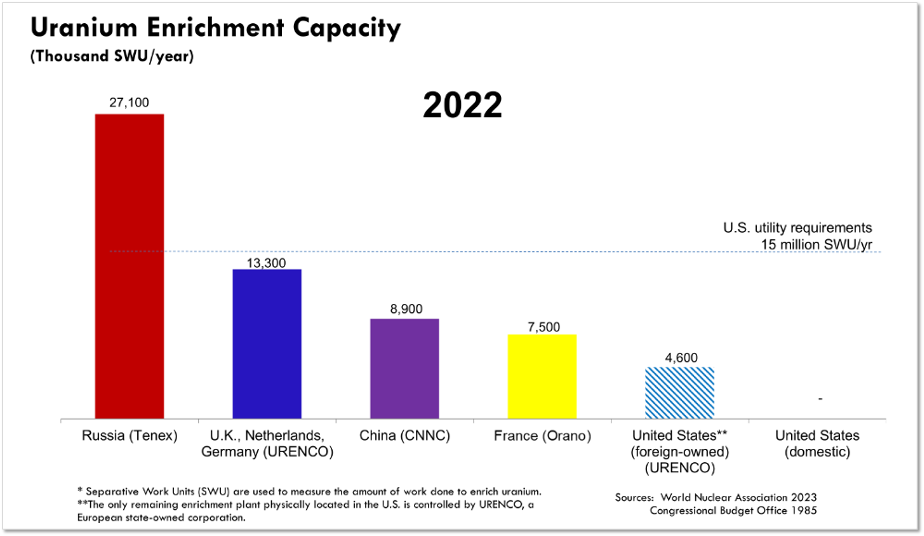

State-owned corporations based in Russia, China, and Europe own nearly 100 percent of the world’s uranium enrichment capacity. None of these foreign state-owned entities can meet U.S. national security requirements for enriched uranium.

In 2019, President Trump took the first step to turn things around. His Department of Energy contracted with a U.S. company to demonstrate an American centrifuge technology in Ohio. It worked, and the technology is up and running, although it’s just a small number of centrifuges so far.

Congress has provided the Department of Energy with about $3 billion to jumpstart U.S. production of enriched uranium. The Biden Administration made initial selections that included two European state-owned enterprises that already dominate the U.S. market, along with the U.S. company operating in Ohio and a handful of startups that have a longer, more uncertain timeline to deployment.

The Trump Administration will soon decide how to allocate the $3 billion, and which projects to fund with it. The options before it are: a lone American company, and multiple dominant foreign players, mainly European. Under the Biden administration, the European enrichment companies were favored. But the U.S. didn’t always rely on foreign companies in this critical sector.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the U.S. government built three huge uranium enrichment plants in Tennessee, Kentucky and Ohio. These plants helped America win the Cold War, power its nuclear navy, and gave the United States a near monopoly on supplying nuclear fuel to allies around the world. This was a key source of global influence for the United States, because countries that wanted to buy nuclear fuel had to agree to America’s standards for safety, security, and non-proliferation.

In the 1970s, European governments invested heavily to create their own uranium enrichment capabilities so that they would not be reliant on the United States for enrichment. The EU subsequently developed an internal policy, the Corfu Declaration, that restricts the ability of U.S. suppliers to provide enriched uranium to the European market.

Over time, Russia and China began to export enriched uranium to the United States, but their state-owned utilities as a rule do not buy U.S. enrichment.

By 1985, the United States had lost its monopoly but was still the dominant player:

In the 1990s, the United States privatized its enrichment operations. That spun out a publicly-traded company, which is now known as Centrus Energy. It is the only publicly-traded enrichment company in a market otherwise dominated by foreign, state-owned, state-subsidized entities. In other words — the only American enrichment company has to compete as a market player, while its foreign competitors enjoy the benefits of state subsidies.

The company leased and operated the government’s two remaining enrichment plants, which relied on inefficient, 1950s gaseous diffusion technology. Cheap imports from Russia — facilitated through agreements negotiated with Russia in the 1990s that resulted in the disposition of highly-enriched uranium from dismantled Russian nuclear weapons — coupled with growing competition from European-owned centrifuge enrichment plants, eventually rendered these plants obsolete. They shut down in 2001 and 2013.

When it comes to fueling civilian nuclear reactors, the United States now depends on foreign, state-owned entities that comprise almost 100 percent of the world’s enrichment capacity. And for the first time since the Roosevelt Administration, the United States lacks the ability to enrich uranium for national security missions.

The State-Owned European enrichers:

- Orano – Owned by the French Government. Orano’s enrichment plant in France represents about 12 percent of the world’s enrichment capacity. They are now expanding in France with €300M from the French government and government-backed loans from the European Investment Bank. Orano has applied for the $3.4B in U.S. government funding to help it build an enrichment plant in Tennessee.

- Urenco – British/Dutch/German consortium. Urenco has a plant in each one of its owner countries (originally paid for by those governments), plus one plant they operate in New Mexico which can meet about one-third of U.S. commercial demand but can’t be used for U.S. national security missions. Urenco is competing with Orano for the $3.4 billion in US funding for its New Mexico plant.

Orano & Urenco both use the European centrifuge design, which they manufacture exclusively in Europe (principally in the Netherlands & Germany) via a joint venture. This means that all advanced manufacturing jobs associated with their centrifuges will be based in Europe. The only exception seems to be Centrus Energy, the U.S. based company which enjoys no state subsidies.

Lucas Nolan is a reporter for Breitbart News covering issues of free speech and online censorship.

Read the full article here