When Tariff Inflation Went Missing, the Fed Invented a New Theory to Explain It

The Federal Reserve’s latest minutes give us more than monetary policy tea leaves. They offer a peek into the mind of an institution trying to explain why its insistence that tariffs would trigger inflation keeps misfiring.

In June, the Fed staff and officials continued to insist that tariffs on imported goods should, in theory, be inflationary. That must be written in the foundation stones of the Eccles Building that President Trump recently toured. But they noted an odd wrinkle: inflation hasn’t responded on cue. Their solution? Firms, they say, are waiting to raise prices—because they’re still working through old, cheaper inventory.

At first blush, this idea might sound plausible. Firms import goods, store them, and sell them. If tariffs make new goods more expensive, perhaps the higher costs only show up once the old stock is gone. This theory has the advantage of being intuitive—and the drawback of being unsupported by virtually everything we know about how retail pricing works.

Prices Don’t Wait for Old Stock to Run Out

The first problem with this is that some of the soundest schools of economics tell us that prices aren’t set by costs at all. They’re set by what consumers are willing to pay. If a firm could charge more, it already would be—tariff or no tariff. As Ludwig von Mises put it, prices determine costs, not the other way around. A tariff might raise input costs, but that doesn’t guarantee prices will rise. It might simply compress margins, reduce output, or drive marginal sellers out of the market. The Fed’s cost-push assumption starts to look shaky once you recall that prices are ultimately demand-driven.

But even if we stay within the so-called New Keynesian synthesis that dominates the Fed’s thinking about economics, the idea that businesses don’t raise prices until they sell out the cheaper inventory doesn’t hold water. In competitive markets, retailers don’t price based on what they paid for inventory last month. They price based on what it will cost to replace that inventory next month. Models and real-world research—including studies of recent tariff episodes—show that price adjustments are forward-looking. Retailers raise prices in anticipation of rising input costs, not in nostalgic tribute to past invoices, according to the theory and research of New Keynesians and their dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (no, really, that’s what they call it, DSGE for short) models.

What might that “something else” be? Demand softness. Competitive pressure. Retailers trying to preserve market share. All valid possibilities. But rather than admit inflation might be falling short of forecasts because tariffs aren’t as inflationary as feared, the Fed appears to be inventing an ad hoc inventory-cycle theory to fill the explanatory gap.

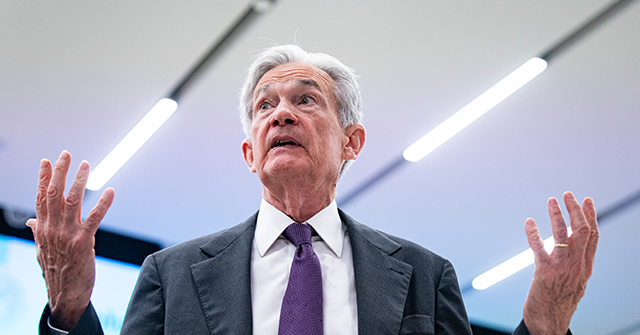

This isn’t the first time the Fed has reverse-engineered a narrative to match disappointing data. During the so-called “transitory” era, we were told supply chains were the culprit. Then it was labor shortages. Now it’s inventory burn-off. The common thread is a refusal to question the assumptions behind the models themselves. They cannot bring themselves to doubt the wisdom in the secret stone tablets that tell Fed Chairman Jerome Powell he must insist that tariffs are inflationary.

If the tariffs didn’t deliver the expected surge in prices, maybe the problem isn’t the timing. Maybe it’s the assumption that tariffs are mechanically inflationary at all. Tariffs may be absorbed by foreign exporters, offset by currency movements, or simply lost in the noise of margin compression and firm-level pricing strategy.

The Fed’s minutes suggest it is still playing catch-up with reality. The danger is that, in clinging to a narrative about delayed inflation, it risks missing what the market is telling it plainly: tariffs have arrived, but the inflation hasn’t. Maybe it’s time to update the theory, break the tablets, not just come up with new excuses and projections that tariffs will definitely raise prices some time real soon.

Read the full article here