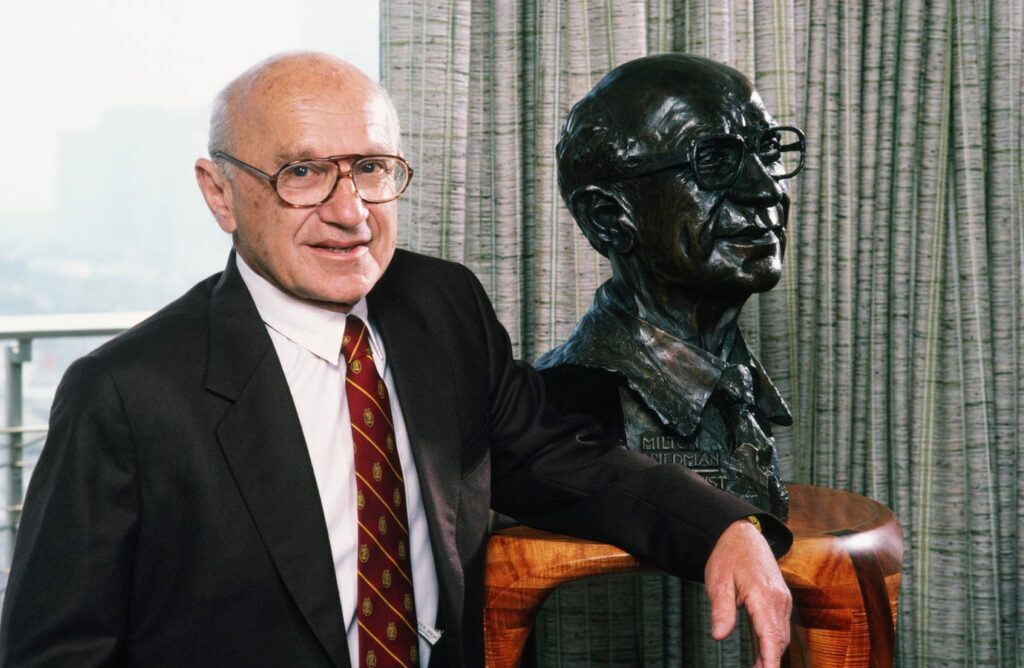

SAN FRANCISCO, CA – 1986: Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman poses with a sculpture of … [+]

In a video that’s gone viral, the late Milton Friedman correctly asserts about inflation that “consumers don’t produce it,” and “producers don’t produce it.” Only for Friedman to go off track with the observation that “too much government spending” does produce inflation.

Ignored by Friedman was that governments aren’t some kind of other capable of extracting spending power from Pluto, rather governments only have the power to spend insofar as they can extract the spending power from the private sector first. All spending, whether by individuals, businesses, or governments, follows production.

For Friedman to then say government spending results in inflation was for him to imply that Say’s Law was anything but, that consumption can be something other than a consequence of production. No. Only Keynesians ascribe an ability of governments to increase demand, but that’s to the everlasting discredit of Keynesianism. Demand not only cannot cause inflation, it has nothing to do with inflation.

To which some will reply that what Friedman actually meant was that governments print money, and then spend the money printed. Supposedly the latter causes inflation. In Friedman’s words from the video, “Inflation is made in Washington because only Washington can create money.” The previous quote reveals how similar Keynesianism and Monetarism are.

To see why, consider what’s accepted (and correct) wisdom on the right: governments have no resources. No, they don’t. They can only spend (or demand) insofar as they have taxable access to production. In Friedman’s case, he’s presuming that government creation of money is the same as government creation of demand. A Keynesian argument, and incorrect.

For Friedman to then imply that government spending could be printed was for him to imply government possessing consumptive power that it quite simply doesn’t have. If governments could just buy things via the printing press, then it’s safe to say that the former Soviet Union would still exist, and countries like Haiti would have debt resembling that of the United States.

Plainly ignored by Friedman was that no one – and this includes governments – buys goods, services and labor with “money.” Production always and everywhere buys production, which explains the Soviet Union’s inability to print funding sufficient for a military that could match the U.S.’s, the lack of spending power in Port-au-Prince today, along with the fact that countries around the world surely have currencies, but their people generally have to have dollars (or a reasonable facsimile of the dollar – think euros, yen, pounds, Swiss francs) if they’d like to actually exchange money for goods and services.

To presume, as Friedman did, that inflation was a function of “too much money chasing too few goods,” was for the Nobel Laureate to imply ferocious market stupidity whereby producers would readily exchange tangible market goods for just any “money.” They didn’t then, nor do they now.

Friedman’s analysis presumed governments printing money, and the printed money circulating on the way to inflation. In reality, printed money generally ceases to circulate precisely because markets are wise, and producers will only accept what commands goods and services commensurate to what they bring to market.

Which is just a reminder that inflation is not a function of increases in so-called “money supply” as Friedman contended. More realistically, it’s the money that’s trusted the most that is circulated most widely and in the greatest amounts. In other words, global circulation of dollars, euros, yen, pounds, and Swiss francs doesn’t signal inflation despite the “supply” of each well exceeding that of Argentine pesos, Haitian gourde, and Congolese francs, rather it signals a relative lack of currency shrinkage (inflation) in the exchange mediums most utilized globally.

Inflation, as always, is not about so-called “money supply,” rather it’s a policy choice. And it’s usually a departure from a standard. FDR chose to devalue the dollar in 1933, and President Nixon chose to sever the dollar’s link to gold in 1971. As the Friedman video circulates to an ever-wider audience, understanding of inflation is in decline.

Read the full article here